by Admin

In Axing mRNA Contract, Trump Delivers Another Blow to US Biosecurity, Former Officials Say

The Trump administration’s cancellation of $766 million in contracts to develop mRNA vaccines against potential pandemic flu viruses is the latest blow to national defense, former health security officials said. They warned that the U.S. could be at the mercy of other countries in the […]

Pharmaceuticals

by Admin

Two Patients Faced Chemo. The One Who Survived Demanded a Test To See if It Was Safe.

JoEllen Zembruski-Ruple, while in the care of New York City’s renowned Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, swallowed the first three chemotherapy pills to treat her squamous cell carcinoma on Jan. 29, her family members said. They didn’t realize the drug could kill her. Six days […]

Pharmaceuticals

by Admin

Trump Exaggerates Speed and Certainty of Prescription Drug Price Reductions

Under a new executive order, prescription drug prices will be reduced “almost immediately.” President Donald Trump, in a May 11 post on Truth Social President Donald Trump expressed high hopes for an executive order to reduce drug prices. On May 11, the day before he […]

Pharmaceuticals

In Axing mRNA Contract, Trump Delivers Another Blow to US Biosecurity, Former Officials Say

by Admin

The Trump administration’s cancellation of $766 million in contracts to develop mRNA vaccines against potential pandemic flu viruses is the latest blow to national defense, former health security officials said. They warned that the U.S. could be at the mercy of other countries in the […]

PharmaceuticalsThe Trump administration’s cancellation of $766 million in contracts to develop mRNA vaccines against potential pandemic flu viruses is the latest blow to national defense, former health security officials said. They warned that the U.S. could be at the mercy of other countries in the next pandemic.

“The administration’s actions are gutting our deterrence from biological threats,” said Beth Cameron, a senior adviser to the Brown University Pandemic Center and a former director at the White House National Security Council. “Canceling this investment is a signal that we are changing our posture on pandemic preparedness,” she added, “and that is not good for the American people.”

Flu pandemics killed up to 103 million people worldwide last century, researchers estimate.

In anticipation of the next big one, the U.S. government began bolstering the nation’s pandemic flu defenses during the George W. Bush administration. These strategies were designed by the security council and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority at the Department of Health and Human Services, among other agencies. The plans rely on rolling out vaccines rapidly in a pandemic. Moving fast hinges on producing vaccines domestically, ensuring their safety, and getting them into arms across the nation through the public health system.

The Trump administration is undermining each of these steps as it guts health agencies, cuts research and health budgets, and issues perplexing policy changes, health security experts said.

Since President Donald Trump took office, at least half of the security council’s staff have been laid off or left, and the future of BARDA is murky. The nation’s top vaccine adviser, Peter Marks, resigned under pressure in March, citing “the unprecedented assault on scientific truth.”

Most recently, Trump’s clawback of funds for mRNA vaccine development put Americans on shakier ground in the next pandemic. “When the need hits and we aren’t ready, no other country will come to our rescue and we will suffer greatly,” said Rick Bright, an immunologist and a former BARDA director.

Countries that produced their own vaccines in the covid-19 pandemic had first dibs on the shots. While the United States, home to Moderna and Pfizer, rolled out second doses of mRNA vaccines in 2021, hundreds of thousands of people in countries that didn’t manufacture vaccines died waiting for them.

The most pertinent pandemic threat today is the bird flu virus H5N1. Researchers around the world were alarmed when it began spreading among cattle in the U.S. last year. Cows are closer to humans biologically than birds, indicating that the virus had evolved to thrive in cells like our own.

As hundreds of herds and dozens of people were infected in the U.S., the Biden administration funded Moderna to develop bird flu vaccines using mRNA technology. As part of the agreement, the U.S. government stipulated it could purchase doses in advance of a pandemic. That no longer stands.

Researchers can make bird flu vaccines in other ways, but mRNA vaccines are developed much more quickly because they don’t rely on finicky biological processes, such as growing elements of vaccines in chicken eggs or cells kept alive in laboratory tanks.

Time matters because flu viruses mutate constantly, and vaccines work better when they match whatever variant is circulating.

Developing vaccines within eggs or cells can take 10 months after the genetic sequence of a variant is known, Bright said. And relying on eggs presents an additional risk when it comes to bird flu because a pandemic could wipe out billions of chickens, crashing egg supplies.

Decades-old methods that rely on inactivated flu viruses are riskier for researchers and time-consuming. Still the Trump administration invested $500 million into this approach, which was largely abandoned by the 1980s after it caused seizures in children.

“This politicized regression is baffling,” Bright said.

A bird flu pandemic may begin quietly in the U.S. if the virus evolves to spread between people but no one is tested at first. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s dashboard suggests that only 10 farmworkers have been tested for the bird flu since March. Because of their close contact with cattle and poultry, farmworkers are at highest risk of infection.

As with many diseases, only a fraction of people with the bird flu become severely sick. So the first sign that the virus is widespread might be a surge in hospital cases.

“We’d need to immediately make vaccines,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

The U.S. government could scale up production of existing bird flu vaccines developed in eggs or cells. However, these vaccines target an older strain of H5N1 and their efficacy against the virus circulating now is unknown.

In addition to the months it takes to develop an updated version within eggs or cells, Rasmussen questioned the ability of the government to rapidly test and license updated shots, with a quarter of HHS staff gone. If the Senate approves Trump’s proposed budget, the agency faces about $32 billion in cuts.

Further, the Trump administration’s cuts to biomedical research and its push to slash grant money for overhead costs could undermine academic hospitals, rendering them unable to conduct large clinical trials. And its cuts to the CDC and to public health funds to states mean that fewer health officials will be available in an emergency.

“You can’t just turn this all back on,” Rasmussen said. “The longer it takes to respond, the more people die.”

Researchers suggest other countries would produce bird flu vaccines first. “The U.S. may be on the receiving end like India was, where everyone — rich people, too — got vaccines late,” said Achal Prabhala, a public health researcher in India at medicines access group AccessIBSA.

He sits on the board of a World Health Organization initiative to improve access to mRNA vaccines in the next pandemic. A member of the initiative, the company Sinergium Biotech in Argentina, is testing an mRNA vaccine against the bird flu. If it works, Sinergium will share the intellectual property behind the vaccine with about a dozen other groups in the program from middle-income countries so they can produce it.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, an international partnership headquartered in Norway, is providing funds to research groups developing rapid-response vaccine technology, including mRNA, in South Korea, Singapore, and France. And CEPI committed up to $20 million to efforts to prepare for a bird flu pandemic. This year, the Indian government issued a call for grant applications to develop mRNA vaccines for the bird flu, warning it “poses a grave public health risk.”

Pharmaceutical companies are investing in mRNA vaccines for the bird flu as well. However, Prabhala says private capital isn’t sufficient to bring early-stage vaccines through clinical trials and large-scale manufacturing. That’s because there’s no market for bird flu vaccines until a pandemic hits.

Limited supplies means the United States would have to wait in line for mRNA vaccines made abroad. States and cities may compete against one another for deals with outside governments and companies, like they did for medical equipment at the peak of the covid pandemic.

“I fear we will once again see the kind of hunger games we saw in 2020,” Cameron said.

In an email response to queries, HHS communications director Andrew Nixon said, “We concluded that continued investment in Moderna’s H5N1 mRNA vaccine was not scientifically or ethically justifiable.” He added, “The decision reflects broader concerns about the use of mRNA platforms—particularly in light of mounting evidence of adverse events associated with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines.”

Nixon did not back up the claim by citing analyses published in scientific journals.

In dozens of published studies, researchers have found that mRNA vaccines against covid are safe. For example, a placebo-controlled trial of more than 30,000 people in the U.S. found that adverse effects of Moderna’s vaccine were rare and transient, whereas 30 participants in the placebo group suffered severe cases of covid and one died.

More recently, a study revealed that three of nearly 20,000 people who got Moderna’s vaccines and booster had significant adverse effects related to the vaccine, which resolved within a few months. Covid, on the other hand, killed four people during the course of the study.

As for concerns about the heart issue, myocarditis, a study of 2.5 million people who got at least one dose of Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine revealed about 2 cases per 100,000 people. Covid causes 10 to 105 myocarditis cases per 100,000.

Nonetheless, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who founded an anti-vaccine organization, has falsely called covid shots “the deadliest vaccine ever made.” And without providing evidence, he said the 1918 flu pandemic “came from vaccine research.”

Politicized mistrust in vaccines has grown. Far more Republicans said they trust Kennedy to provide reliable information on vaccines than their local health department or the CDC in a recent KFF poll: 73% versus about half.

Should the bird flu become a pandemic in the next few years, Rasmussen said, “we will be screwed on multiple levels.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

Two Patients Faced Chemo. The One Who Survived Demanded a Test To See if It Was Safe.

JoEllen Zembruski-Ruple, while in the care of New York City’s renowned Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, swallowed the first three chemotherapy pills to treat her squamous cell carcinoma on Jan. 29, her family members said. They didn’t realize the drug could kill her. Six days […]

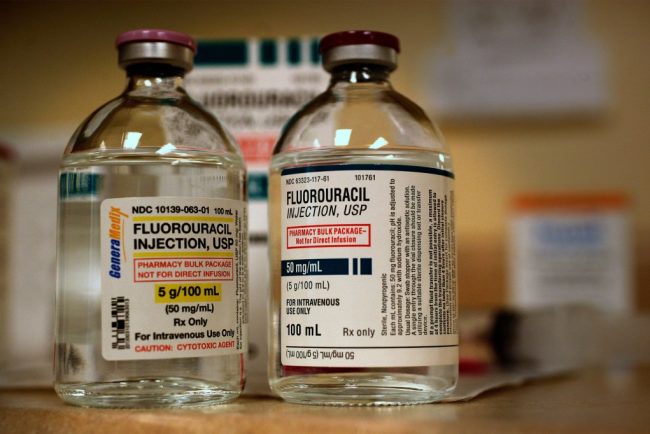

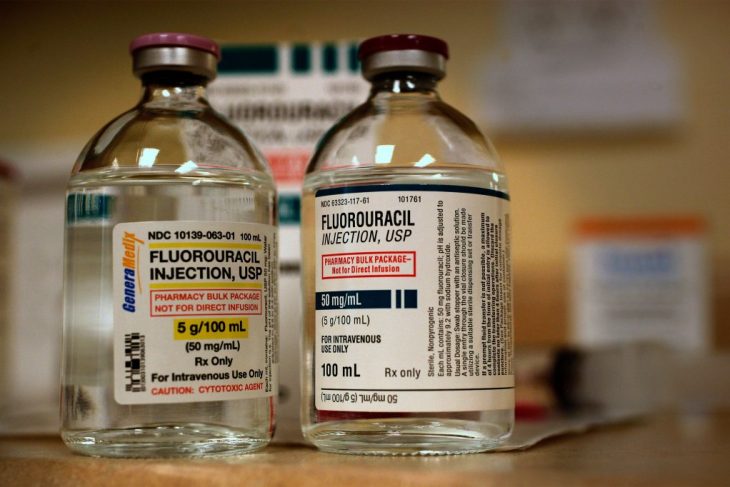

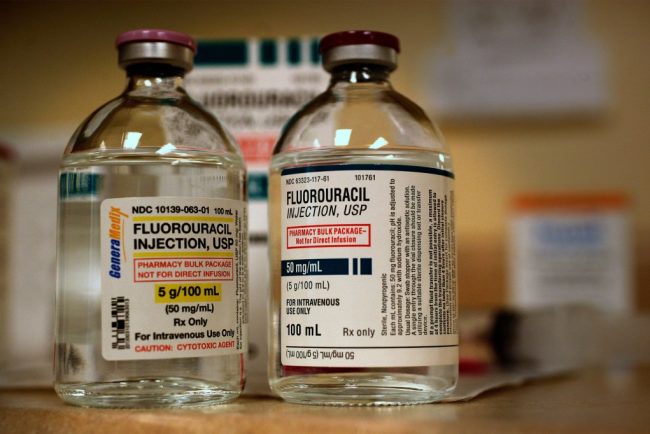

PharmaceuticalsJoEllen Zembruski-Ruple, while in the care of New York City’s renowned Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, swallowed the first three chemotherapy pills to treat her squamous cell carcinoma on Jan. 29, her family members said. They didn’t realize the drug could kill her.

Six days later, Zembruski-Ruple went to Sloan Kettering’s urgent care department to treat sores in her mouth and swelling around her eyes. The hospital diagnosed oral yeast infection and sent her home, her sister and partner said. Two days later, they said, she returned in agony — with severe diarrhea and vomiting — and was admitted. “Enzyme deficiency,” Zembruski-Ruple texted a friend.

The 65-year-old, a patient advocate who had worked for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and other groups, would never go home.

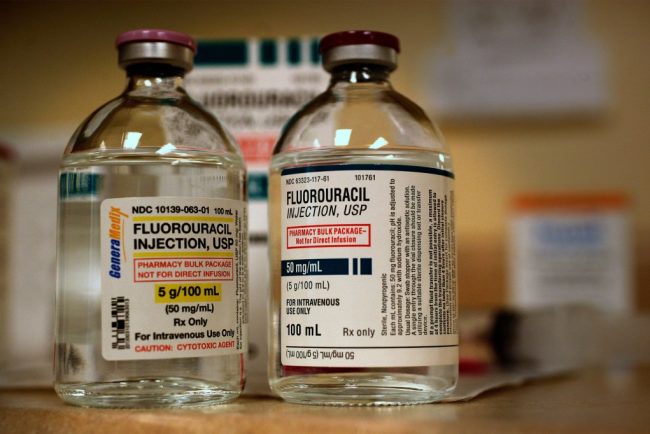

Covered in bruises and unable to swallow or talk, she eventually entered hospice care and died March 25 from the very drug that was supposed to extend her life, said her longtime partner, Richard Khavkine. Zembruski-Ruple was deficient in the enzyme that metabolizes capecitabine, the chemotherapy drug she took, said Khavkine and Susan Zembruski, one of her sisters. Zembruski-Ruple was among about 1,300 Americans each year who die from the toxic effects of that pill or its cousin, the IV drug fluorouracil known as 5-FU.

Doctors can test for the deficiency — and then either switch drugs or lower the dosage if patients have a genetic variant that carries risk. The FDA approved an antidote in 2015, but it’s expensive and must be administered within four days of the first chemotherapy treatment.

Newer cancer drugs sometimes include a companion diagnostic to determine whether a drug works with an individual patient’s genetics. But 5-FU went on the market in 1962 and sells for about $17 a dose; producers of its generic aren’t seeking approval for toxicity tests, which typically cost hundreds of dollars. Doctors have only gradually understood which gene variants are dangerous in which patients, and how to deal with them, said Alan Venook, a colorectal and liver cancer specialist at the University of California-San Francisco.

By the time Zembruski-Ruple’s doctors told her she had the deficiency, she had been on the drug for eight days, said Khavkine, who watched over his partner with her sister throughout the seven-week ordeal.

Khavkine said he “would have asked for the test” if he had known about it, but added “nobody told us about the possibility of this deficiency.” Zembruski-Ruple’s sister also said she wasn’t warned about the fatal risks of the chemo, or told about the test.

“They never said why they didn’t test her,” Zembruski said. “If the test existed, they should have said there is a test. If they said, ‘Insurance won’t cover it,’ I would have said, ‘Here’s my credit card.’ We should have known about it.”

Guidance Moves at a Glacial Pace

Despite growing awareness of the deficiency, and an advocacy group made up of grieving friends and relatives who push for routine testing of all patients before they take the drug, the medical establishment has moved slowly.

A panel of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, or NCCN — specialists from Sloan Kettering and other top research centers — until recently did not recommend testing, and the FDA does not require it.

In response to a query from KFF Health News about its policy, Sloan Kettering spokesperson Courtney Nowak said the hospital treats patients “in accordance with NCCN guidelines.” She said the hospital would not discuss a patient’s care.

On Jan. 24, the FDA issued a warning about the enzyme deficiency in which it urged health care providers to “inform patients prior to treatment” about the risks of taking 5-FU and capecitabine.

On March 31 — six days after Zembruski-Ruple’s death — the network’s expert panel for most gastrointestinal cancers took a first step toward recommending testing for the deficiency.

Worried that President Donald Trump’s FDA might do nothing, Venook said, the panel — whose guidance shapes the practices of oncologists and health insurers — recommended that doctors consider testing before dosing patients with 5-FU or capecitabine.

However, its guidance stated that “no specific test is recommended at this time,” citing a lack of data to “inform dose adjustments.”

Sloan Kettering “will consider this guidance in developing personalized treatment plans for each patient,” Nowak told KFF Health News.

The new NCCN guidance was “not the blanket recommendation we were working toward, but it is a major step toward our ultimate goal,” said Kerin Milesky, a public health official in Brewster, Massachusetts, who’s part of an advocacy group for testing. Her husband, Larry, died two years ago at age 73 after a single treatment of capecitabine.

European drug regulators began urging oncologists to test patients for deficiency in May 2020. Patients with potentially risky genetics are started on a half-dose of the cancer drug. If they suffer no major toxicity, the dose is increased.

A Lifesaving Ultimatum?

Emily Alimonti, a 42-year-old biotech salesperson in upstate New York, chose that path before starting capecitabine treatment in December. She said her doctors — including an oncologist at Sloan Kettering — told her they didn’t do deficiency testing, but Alimonti insisted. “Nope,” she said. “I’m not starting it until I get the test back.”

The test showed that Alimonti had a copy of a risky gene variant, so doctors gave her a lower dose of the drug. Even that has been hard to tolerate; she’s had to skip doses because of low white blood cell counts, Alimonti said. She still doesn’t know whether her insurer will cover the test.

Around 300,000 people are treated with 5-FU or capecitabine in the United States each year, but its toxicity could well have prevented FDA approval were it up for approval today. Short of withdrawing a drug, however, U.S. regulators have little power to manage its use. And 5-FU and capecitabine are still powerful tools against many cancers.

At a January workshop that included FDA officials and cancer specialists, Venook, the NCCN panel’s co-chair, asked whether it was reasonable to recommend that doctors obtain a genetic test “without saying what to do with the result.”

But Richard Pazdur, the FDA’s top cancer expert, said it was time to end the debate and commence testing, even if the results could be ambiguous. “If you don’t have the information, how do you have counseling?” he asked.

Two months later, Venook’s panel changed course. The price of tests has fallen below $300 and results can be returned as soon as three days, Venook said. Doubts about the FDA’s ability to further confront the issue spurred the panel’s change of heart, he said.

“I don’t know if FDA is going to exist tomorrow,” Venook told KFF Health News. “They’re taking a wrecking ball to common sense, and that’s one of the reasons we felt we had to go forward.”

On May 20, the FDA posted a Federal Register notice seeking public input on the issue, a move that suggested it was considering further action.

Venook said he often tests his own patients, but the results can be fuzzy. If the test finds two copies of certain dangerous gene variants in a patient, he avoids using the drug. But such cases are rare — and Zembruski-Ruple was one of them, according to her sister and Khavkine.

Many more patients have a single copy of a suspect gene, an ambiguous result that requires clinical judgment to assess, Venook said.

A full-gene scan would provide more information but adds expense and time, and even then the answer may be murky, Venook said. He worries that starting patients on lower doses could mean fewer cures, especially for newly diagnosed colon cancer patients.

Power Should Rest With Patients

Scott Kapoor, a Toronto-area emergency room physician whose brother Anil, a much-loved urologist and surgeon, died of 5-FU toxicity at age 58 in 2023, views Venook’s arguments as medical paternalism. Patients should decide whether to test and what to do with the results, he said.

“What’s better — don’t tell the patient about the test, don’t test them, potentially kill them in 20 days?” he said. “Or tell them about the testing while warning that potentially the cancer will kill them in a year?”

“People say oncologists don’t know what to do with the information,” said Karen Merritt, whose mother died after an infusion of 5-FU in 2014. “Well, I’m not a doctor, but I can understand the Mayo Clinic report on it.”

The Mayo Clinic recommends starting patients on half a dose if they have one suspect gene variant. And “the vast majority of patients will be able to start treatment without delays,” Daniel Hertz, a clinical pharmacologist from the University of Michigan, said at the January meeting.

Some hospitals began testing after patients died because of the deficiency, said Lindsay Murray, of Andover, Massachusetts, who has advocated for widespread testing since her mother was treated with capecitabine and died in 2021.

In some cases, Venook said, relatives of dead patients have sued hospitals, leading to settlements.

Kapoor said his brother — like many patients of non-European origin — had a gene variant that hasn’t been widely studied and isn’t included in most tests. But a full-gene scan would have detected it, Kapoor said, and such scans can also be done for a few hundred dollars.

The cancer network panel’s changed language is disappointing, he said, though “better than nothing.”

In video tributes to Zembruski-Ruple, her friends, colleagues, and clients remembered her as kind, helpful, and engaging. “JoEllen was beautiful both inside and out,” said Barbara McKeon, a former colleague at the MS Society. “She was funny, creative, had a great sense of style.”

“JoEllen had this balance of classy and playful misbehavior,” psychotherapist Anastatia Fabris said. “My beautiful, vibrant, funny, and loving friend JoEllen.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

Trump Exaggerates Speed and Certainty of Prescription Drug Price Reductions

Under a new executive order, prescription drug prices will be reduced “almost immediately.” President Donald Trump, in a May 11 post on Truth Social President Donald Trump expressed high hopes for an executive order to reduce drug prices. On May 11, the day before he […]

PharmaceuticalsUnder a new executive order, prescription drug prices will be reduced “almost immediately.”

President Donald Trump, in a May 11 post on Truth Social

President Donald Trump expressed high hopes for an executive order to reduce drug prices.

On May 11, the day before he held a White House event to sign the executive order, Trump posted on Truth Social, “Prescription Drug and Pharmaceutical prices will be REDUCED, almost immediately, by 30% to 80%.”

However, the executive order’s text, unveiled May 12, undercut the president’s description of how soon consumers could experience this potential boon.

The idea of the executive order, he said, was to lower high prescription drug costs in the U.S. to levels more typical in other countries.

“We’re going to equalize,” Trump said at the order signing. “We’re all going to pay the same. We’re going to pay what Europe’s going to pay.”

Experts said Trump’s action could lower the cost of prescription drugs, perhaps by the 30% to 80% Trump said, but they cautioned that the order’s required procedural steps would make it far from an immediate fix.

The executive order says that within 30 days, administration officials must determine and communicate to drugmakers “most-favored-nation price targets,” to push the companies to “bring prices for American patients in line with comparably developed nations.”

After an unspecified period of time, the administration will gauge whether “significant progress” toward lower pricing has been achieved. If not, the order requires the secretary of Health and Human Services to “propose a rulemaking plan to impose most-favored-nation pricing,” which could take months or years to take effect.

“Executive orders are wish lists,” said Joseph Antos, a senior fellow emeritus in health care policy at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. The order “hopes that manufacturers will unilaterally lower U.S. prices. The legal authority to intervene in the market is unclear if this implausible scenario doesn’t happen.”

When contacted for comment, the White House did not provide evidence that the executive order would provide immediate results.

Why Do Americans Pay More for Prescriptions?

There is wide agreement that drug prices are unusually high in the U.S. The prices Americans pay for pharmaceuticals are nearly three times the average among a group of other industrialized countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

A study by the Rand Corp., a nonpartisan research organization, found that, across all drugs, U.S. prices were 2.78 times as high as the average prices across 33 OECD countries. The gap was even wider for brand-name drugs, with U.S. prices averaging 4.22 times as much.

The U.S. has lower prices than comparable nations for unbranded, generic drugs, which account for about 90% of filled prescriptions in the U.S. But generics account for only a fifth of U.S. prescription drug spending.

Experts cite several reasons for this pricing discrepancy.

One is that the U.S. has more limited price negotiation with drug manufacturers than other countries do. Often, if another country fails to find the extra cost of a new drug is justified by improved results, it’ll reject the drug application. Some countries also set price controls.

Another factor is patent exclusivity. Over the years, U.S. pharmaceutical companies have used strong legal protections to amass patents that can keep generic competitors from the marketplace.Drug companies have also argued that high prices help pay for research and development of new and improved pharmaceuticals. When Trump released the executive order, Stephen J. Ubl, president and CEO of the drug industry group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, said in a statement, “It would mean less treatments and cures and would jeopardize the hundreds of billions our member companies are planning to invest in America.” (In Trump’s May 13 interview with Fox News’ Sean Hannity, Trump offered a different picture of what drug company officials have told him; he said they agreed “it’s time” to lower U.S. prices.)

Recent studies have cast doubt on the idea that high prices pay for research and development. A 2023 study found that from 1999 to 2018, the world’s 15 largest biopharmaceutical companies spent more on selling and general administrative activities, which include marketing, than on research and development. The study also said most new medicines developed during this period offered little to no clinical benefit over existing treatments.

The long-standing reality of high U.S. drug prices has driven Democratic and Republican efforts to bring them down. Then-President Joe Biden signed legislation to require Medicare, the federal health care program that covers Americans over 65, to negotiate prices with the makers of some popular, high-cost medicines. And Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) has made lowering drug prices a cornerstone issue during his political career.

During his first term, Trump sought to lower prices for certain drugs under Medicare, but the courts blocked the move on procedural grounds.

Trump’s drug-price push could attract bipartisan support, experts said.

Jonathan Cohn, who has worked for several left-of-center media outlets and wrote two books on health care policy, offered measured praise for Trump’s executive order in The Bulwark, a publication generally critical of Trump, calling it “a serious policy initiative, one that credible people think could bring some relief on drug prices.”

Andrew Mulcahy, a Rand Corp. senior health economist, said one part of Trump’s statement — the possibility of a 30% to 80% price reduction — is plausible.

“Of course, the devil’s in the policy design and implementation details,” Mulcahy said. “But at first blush, a savings of roughly two-thirds on what we spend now for drugs seems in line” with what Rand’s research has shown.

What Would Trump’s Executive Order Do?

Referring to high U.S. drug prices, Trump told Hannity that “I ended it” by issuing the executive order. But that’s not how the order is structured.

The executive order makes plain that any actions will not happen quickly.

“That ‘almost’ in ‘almost immediately’ is doing a lot of work,” Mulcahy said, referring to Trump’s statement.

The executive order also could face court challenges, just as Trump’s first-term executive order did.

“It seems unlikely that the federal government can set prices for drugs outside of the Medicare program,” Antos said. If Trump wants reduced prices to benefit all U.S. consumers, experts said, Congress will likely have to pass new legislation. While executive orders direct federal agencies what to do, requiring action from privately owned companies likely would require legislation passed by Congress, experts said.

If Congress gets involved, that will not only tack on extra time, but it also could draw opposition from the Republican majority in one or both chambers. Historically, Antos said, “federal price controls are anathema for many Republicans in Congress.”

Our Ruling

Trump said that, because of his new executive order, prescription drug prices would be reduced “almost immediately.”

Experts said that if the goals of the executive order are achieved, price reductions would not happen “almost immediately.”

The order sets out a 30-day period to develop pricing targets for drugmakers, followed by an unspecified amount of time to see if companies achieve the targets. If they don’t, a formal rulemaking process would begin, requiring months or even years. And if Trump intends to lower prices for all consumers, not only those who have federal coverage such as Medicare, Congress will likely have to pass a law to do it.

Trump gives the impression that Americans will shortly see steep decreases in what they pay for prescription drugs. But even if the executive order acts as intended — which would require a lot to go right — it could take months or years.

The statement contains an element of truth but ignores evidence that would give a different impression. We rate it Mostly False.

Sources

Donald Trump, Truth Social post, May 11, 2025

White House, “Delivering Most-Favored-Nation Prescription Drug Pricing to American Patients,” May 12, 2025

Rand Corp., “International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Estimates Using 2022 Data,” February 2024

Government Accountability Office, “U.S. Prices for Selected Brand Drugs Were Higher on Average Than Prices in Australia, Canada, and France,” March 2021

The BMJ, “High Drug Prices Are Not Justified by Industry’s Spending on Research and Development,” Feb. 15, 2023

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, “PhRMA Statement on Most Favored Nation Executive Order,” May 12, 2025

USA Today, “RFK Jr. Spars With Bernie Sanders Over Who Did Most To Curb Prescription Drug Prices,” May 12, 2025

The Associated Press, “Trump Plan To Curb Drug Costs Dealt Setback in Court,” Dec. 23, 2020

The Associated Press, “White House Says Prescription Drug Deals Will Produce Billions in Savings for Taxpayers, Seniors,” Aug. 15, 2024

PolitiFact, “For the Most Part, the US Pays Double for Prescriptions Compared With Other Countries, as Biden Says,” March 4, 2024

Email interview with Joseph Antos, senior fellow emeritus in health care policy at the American Enterprise Institute, May 12, 2025

Email interview with Andrew Mulcahy, senior health economist with Rand Corp., May 12, 2025

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

How Trump Aims To Slash Federal Support for Research, Public Health, and Medicaid

Health care has proved a vulnerable target for the firehose of cuts and policy changes President Donald Trump ordered in the name of reducing waste and improving efficiency. But most of the impact isn’t as tangible as, say, higher egg prices at the grocery store. […]

PharmaceuticalsHealth care has proved a vulnerable target for the firehose of cuts and policy changes President Donald Trump ordered in the name of reducing waste and improving efficiency. But most of the impact isn’t as tangible as, say, higher egg prices at the grocery store.

One thing experts from a wide range of fields, from basic science to public health, agree on: The damage will be varied and immense. “It’s exceedingly foolish to cut funding in this way,” said Harold Varmus, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist and former director of both the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

The blaze of cuts have yielded nonsensical and perhaps unintended consequences. Consider instances in which grant funding gets canceled after two years of a three-year project. That means, for example, that $2 million has already been spent but there will be no return on that investment.

Some of the targeted areas are not administration priorities. That includes the abrupt termination of studies on long covid, which afflicts more than 100,000 Americans, and the interruption of work on mRNA vaccines, which hold promise not just in infectious disease but also in treating cancer.

While charitable dollars have flowed in to plug some gaps, “philanthropy cannot replace federal funding,” said Dustin Sposato, communications manager for the Science Philanthropy Alliance, a group that works to boost support from charities for basic science research.

Here are critical ways in which Trump administration cuts — proposed and actual — could affect American health care and, more important, the health of American patients.

Cuts to the National Institutes of Health: The Trump administration has cut $2.3 billion in new grant funding since its term began, as well as terminated existing grants on a wide range of topics — vaccine hesitancy, HIV/AIDS, and covid-19 — that do not align with its priorities. National Institutes of Health grants do have yearly renewal clauses, but it is rare for them to be terminated, experts say. The administration has also cut “training grants” for young scientists to join the NIH.

Why It Matters: The NIH has long been a crucible of basic science research — the kind of work that industry generally does not do. Most pharmaceutical patents have their roots in work done or supported by the NIH, and many scientists at pharmaceutical manufacturers learned their craft at institutions supported by the NIH or at the NIH itself. The termination of some grants will directly affect patients since they involved ongoing clinical studies on a range of conditions, including pediatric cancer, diabetes, and long covid. And, more broadly, cuts in public funding for research could be costly in the longer term as a paucity of new discoveries will mean fewer new products: A 25% cut to public research and development spending would reduce the nation’s economic output by an amount comparable to the decline in gross domestic product during the Great Recession, a new study found.

Cuts to Universities: The Trump administration also tried to deal a harrowing blow — currently blocked by the courts — to scientific research at universities by slashing extra money that accompanies research grants for “indirect costs,” like libraries, lab animal care, support staff, and computer systems.

Why It Matters: Wealthier universities may find the funds to make up for draconian indirect cost cuts. But poorer ones — and many state schools, many of them in red states — will simply stop doing research. A good number of crucial discoveries emerge from these labs. “Medical research is a money-losing proposition,” said one state school dean with former ties to the Ivies. (The dean requested anonymity because his current employer told him he could not speak on the record.) “If you want to shut down research, this will do it, and it will go first at places like the University of Tennessee and the University of Arkansas.” That also means fewer opportunities for students at state universities to become scientists.

Cuts to Public Health: These hits came in many forms. The administration has cut or threatened to cut long-standing block grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; covid-related grants; and grants related to diversity, equity, and inclusion activities — which often translated into grants to improve health care for the underserved. Though the covid pandemic has faded, those grants were being used by states to enhance lab capacity to improve detection and surveillance. And they were used to formally train the nation’s public health workforce, many of whom learn on the job.

Why It Matters: Public health officials and researchers were working hard to facilitate a quicker, more thoughtful response to future pandemics, of particular concern as bird flu looms and measles is having a resurgence. Mati Hlatshwayo Davis, the St. Louis health director, had four grants canceled, three in one day. One grant that fell under the covid rubric included programs to help community members make lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of hypertension and diabetes — the kind of chronic diseases that Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has said he will focus on fighting. Others paid the salaries of support staff for a wide variety of public health initiatives. “What has been disappointing is that decisions have been made without due diligence,” she said.

Health-Related Impact of Tariffs: Though Trump has exempted prescription drugs from his sweeping tariffs on most imports thus far, he has not ruled out the possibility of imposing such tariffs. “It’s a moving target,” said Michael Strain, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, noting that since high drug prices are already a burden, adding any tax to them is problematic.

Why It Matters: That supposed exemption doesn’t fully insulate American patients from higher costs. About two-thirds of prescription drugs are already manufactured in the U.S. But their raw materials are often imported from China — and those enjoy no tariff exemption. Many basic supplies used in hospitals and doctors’ offices — syringes, surgical drapes, and personal protective equipment — are imported, too. Finally, even if the tariffs somehow don’t themselves magnify the price to purchase ingredients and medical supplies, Americans may suffer: Across-the-board tariffs on such a wide range of products, from steel to clothing, means fewer ships will be crossing the Pacific to make deliveries — and that means delays. “I think there’s an uncomfortably high probability that something breaks in the supply chain and we end up with shortages,” Strain said.

Changes to Medicaid: Trump has vowed to protect Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for Americans with low incomes and disabilities. But House Republicans have eyed the program as a possible source of offsets to help pay for what Trump calls “the big, beautiful bill” — a sweeping piece of budget legislation to extend his 2017 tax cuts. The amount of money GOP leaders have indicated they could squeeze from Medicaid, which now covers about 20% of Americans, has been in the hundreds of billions of dollars. But deep cuts are politically fraught.

To generate some savings, administration officials have at times indicated they are open to at least some tweaks to Medicaid. One idea on the table — work requirements — would require adults on Medicaid to be working or in some kind of job training. (Nearly two-thirds of Medicaid recipients ages 19-64 already work.)

Why It Matters: In 2024 the uninsured rate was 8.2%, near the all-time low, in large part because of the Medicaid expansion under the 2010 Affordable Care Act. Critics say work requirements are a backhanded way to slim down the Medicaid rolls, since the paperwork requirements of such programs have proved so onerous that eligible people drop out, causing the uninsured rate to rise. A Congressional Budget Office report estimates that the proposed change would reduce coverage by at least 7.7 million in a decade. This leads to higher rates of uncompensated care, putting vulnerable health care facilities — think rural hospitals — at risk.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

Pharmacists Stockpile Most Common Drugs on Chance of Targeted Trump Tariffs

In the dim basement of a Salt Lake City pharmacy, hundreds of amber-colored plastic pill bottles sit stacked in rows, one man’s defensive wall in a tariff war. Independent pharmacist Benjamin Jolley and his colleagues worry that the tariffs, aimed at bringing drug production to […]

PharmaceuticalsIn the dim basement of a Salt Lake City pharmacy, hundreds of amber-colored plastic pill bottles sit stacked in rows, one man’s defensive wall in a tariff war.

Independent pharmacist Benjamin Jolley and his colleagues worry that the tariffs, aimed at bringing drug production to the United States, could instead drive companies out of business while raising prices and creating more of the drug shortages that have plagued American patients for several years.

Jolley bought six months’ worth of the most expensive large bottles, hoping to shield his business from the 10% across-the-board tariffs on imported goods that President Donald Trump announced April 2. Now with threats of additional tariffs targeting pharmaceuticals, Jolley worries that costs will soar for the medications that will fill those bottles.

In principle, Jolley said, using tariffs to push manufacturing from China and India to the U.S. makes sense. In the event of war, China could quickly stop all exports to the United States.

“I understand the rationale for tariffs. I’m not sure that we’re gonna do it the right way,” Jolley said. “And I am definitely sure that it’s going to raise the price that I pay my suppliers.”

Squeezed by insurers and middlemen, independent pharmacists such as Jolley find themselves on the front lines of a tariff storm. Nearly everyone down the line — drugmakers, pharmacies, wholesalers, and middlemen — opposes most tariffs.

Slashing drug imports could trigger widespread shortages, experts said, because of America’s dependence on Chinese- and Indian-made chemical ingredients, which form the critical building blocks of many medicines. Industry officials caution that steep tariffs on raw materials and finished pharmaceuticals could make drugs more expensive.

“Big ships don’t change course overnight,” said Robin Feldman, a UC Law San Francisco professor who writes about prescription drug issues. “Even if companies pledge to bring manufacturing home, it will take time to get them up and running. The key will be to avoid damage to industry and pain to consumers in the process.”

Trump on April 8 said he would soon announce “a major tariff on pharmaceuticals,” which have been largely tariff-free in the U.S. for 30 years.

“When they hear that, they will leave China,” he said. The U.S. imported $213 billion worth of medicines in 2024 — from China but also India, Europe, and other areas.

Trump’s statement sent drugmakers scrambling to figure out whether he was serious, and whether some tariffs would be levied more narrowly, since many parts of the U.S. drug supply chain are fragile, drug shortages are common, and upheaval at the FDA leaves questions about whether its staffing is adequate to inspect factories, where quality problems can lead to supply chain crises.

On May 12, Trump signed an executive order asking drugmakers to bring down the prices Americans pay for prescriptions, to put them in line with prices in other countries.

Meanwhile, pharmacists predict even the 10% tariffs Trump has demanded will hurt: Jolley said a potential increase of up to 30 cents a vial is not a king’s ransom, but it adds up when you’re a small pharmacy that fills 50,000 prescriptions a year.

“The one word that I would say right now to describe tariffs is ‘uncertainty,’” said Scott Pace, a pharmacist and owner of Kavanaugh Pharmacy in Little Rock, Arkansas.

To weather price fluctuations, Pace stocked up on the drugs his pharmacy dispenses most.

“I’ve identified the top 200 generics in my store, and I have basically put 90 days’ worth of those on the shelf just as a starting point,” he said. “Those are the diabetes drugs, the blood pressure medicines, the antibiotics — those things that I know folks will be sicker without.”

Pace said tariffs could be the death knell for the many independent pharmacies that exist on “razor-thin margins” — unless reimbursements rise to keep up with higher costs.

Unlike other retailers, pharmacies can’t pass along such costs to patients. Their payments are set by health insurers and pharmacy benefit managers largely owned by insurance conglomerates, who act as middlemen between drug manufacturers and purchasers.

Neal Smoller, who employs 15 people at his Village Apothecary in Woodstock, New York, is not optimistic.

“It’s not like they’re gonna go back and say, well, here’s your 10% bump because of the 10% tariff,” he said. “Costs are gonna go up and then the sluggish responses from the PBMs — they’re going to lead us to lose more money at a faster rate than we already are.”

Smoller, who said he has built a niche selling vitamins and supplements, fears that FDA firings will mean fewer federal inspections and safety checks.

“I worry that our pharmaceutical industry becomes like our supplement industry, where it’s the wild West,” he said.

Narrowly focused tariffs might work in some cases, said Marta Wosińska, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Center on Health Policy. For example, while drug manufacturing plants can cost $1 billion and take three to five years to set up, it would be relatively cheap to build a syringe factory — a business American manufacturers abandoned during the covid-19 pandemic because China was dumping its products here, Wosińska said.

It’s not surprising that giants such as Novartis and Eli Lilly have promised Trump they’ll invest billions in U.S. plants, she said, since much of their final drug product is made here or in Europe, where governments negotiate drug prices. The industry is using Trump’s tariff saber-rattling as leverage; in an April 11 letter, 32 drug companies demanded European governments pay them more or face an exodus to the United States.

Brandon Daniels, CEO of supply chain company Exiger, is bullish on tariffs. He thinks they could help bring some chemical manufacturing back to the U.S., which, when coupled with increased use of automation, would reduce the labor advantages of China and India.

“You’ve got real estate in North Texas that’s cheaper than real estate in Shenzhen,” he said at an economic conference April 25 in Washington, referring to a major Chinese chemical manufacturing center.

But Wosińska said no amount of tariffs will compel makers of generic drugs, responsible for 90% of U.S. prescriptions, to build new factories in the U.S. Payment structures and competition would make it economic suicide, she said.

Several U.S. generics firms have declared bankruptcy or closed U.S. factories over the past decade, said John Murphy, CEO of the Association for Accessible Medicines, the generics trade group. Reversing that trend won’t be easy and tariffs won’t do it, he said.

“There’s not a magic level of tariffs that magically incentivizes them to come into the U.S.,” he said. “There is no room to make a billion-dollar investment in a domestic facility if you’re going to lose money on every dose you sell in the U.S. market.”

His group has tried to explain these complexities to Trump officials, and hopes word is getting through. “We’re not PhRMA,” Murphy said, referring to the powerful trade group primarily representing makers of brand-name drugs. “I don’t have the resources to go to Mar-a-Lago to talk to the president myself.”

Many of the active ingredients in American drugs are imported. Fresenius Kabi, a German company with facilities in eight U.S. states to produce or distribute sterile injectables — vital hospital drugs for cancer and other conditions — complained in a letter to U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer that tariffs on these raw materials could paradoxically lead some companies to move finished product manufacturing overseas.

Fresenius Kabi also makes biosimilars, the generic forms of expensive biologic drugs such as Humira and Stelara. The United States is typically the last developed country where biosimilars appear on the market because of patent laws.

Tariffs on biosimilars coming from overseas — where Fresenius makes such drugs — would further incentivize U.S. use of more expensive brand-name biologics, the March 11 letter said. Biosimilars, which can cost a tenth of the original drug’s price, launch on average 3-4 years later in the U.S. than in Canada or Europe.

In addition to getting cheaper knockoff drugs faster, European countries also pay far less than the United States for brand-name products. Paradoxically, Murphy said, those same countries pay more for generics.

European governments tend to establish more stable contracts with makers of generics, while in the United States, “rabid competition” drives down prices to the point at which a manufacturer “maybe scrimps on product quality,” said John Barkett, a White House Domestic Policy Council member in the Biden administration.

As a result, Wosińska said, “without exemptions or other measures put in place, I really worry about tariffs causing drug shortages.”

Smoller, the New York pharmacist, doesn’t see any upside to tariffs.

“How do I solve the problem of caring for my community,” he said, “but not being subject to the emotional roller coaster that is dispensing hundreds of prescriptions a day and watching every single one of them be a loss or 12 cents profit?”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': GOP Tries To Cut Billions in Health Benefits

The Host Julie Rovner KFF Health News @jrovner @julierovner.bsky.social Read Julie’s stories. Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the […]

PharmaceuticalsThe Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

After all-night markups, two key House committees approved GOP budget legislation that would cut hundreds of billions of dollars from federal health programs over the next decade, mostly from the Medicaid program for people with low incomes or disabilities. The legislation is far from a done deal, though, with at least one Republican senator voicing opposition to Medicaid cuts.

Meanwhile, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. testified before Congress for the first time since taking office. In sometimes surprisingly combative exchanges with lawmakers in the House and Senate, Kennedy denied cutting programs despite evidence to the contrary and said at one point that he doesn’t think Americans “should be taking medical advice from me.”

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Julie Appleby of KFF Health News, Joanne Kenen of the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health and Politico Magazine, and Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico.

Panelists

Julie Appleby

KFF Health News

Joanne Kenen

Johns Hopkins University and Politico

Alice Miranda Ollstein

Politico

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- House Republicans this week released — then quickly ushered through committee — major legislation that would make deep cuts to federal spending while funding President Donald Trump’s domestic priorities, including renewing tax cuts and boosting border security. A preliminary estimate by the Congressional Budget Office found the bill would cut at least $715 billion from federal health spending over 10 years — with most of that money coming from the Medicaid program.

- Overall, the House GOP’s proposal would make it harder to enroll, and stay enrolled, in Medicaid and Affordable Care Act coverage. Among other changes, the bill would impose a requirement that nondisabled adults (with some exceptions) work, volunteer, or study at least 80 hours per month to be eligible for coverage. But Democrats and patient advocates point to evidence that, rather than encouraging employment, such a mandate results in more people losing or dropping coverage under burdensome paperwork requirements.

- Republicans also declined to extend the enhanced tax credits introduced during the covid-19 pandemic that help many people afford ACA marketplace coverage. Those tax credits expire at the end of the year, and premiums are expected to balloon, which could prompt many people not to renew their coverage.

- And Kennedy’s appearances on Capitol Hill this week provided Congress the first opportunity to question the health secretary since he assumed his post. He was grilled by Democrats about vaccines, congressionally appropriated funds, agency firings, and much more.

Plus, for “extra credit,” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: The New York Times’ “Elizabeth Holmes’s Partner Has a New Blood-Testing Start-Up,” by Rob Copeland.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: ProPublica’s “He Became the Face of Georgia’s Medicaid Work Requirement. Now He’s Fed Up With It.” by Margaret Coker, The Current.

Julie Appleby: Scientific American’s “How Trump’s National Weather Service Cuts Could Cost Lives,” by Andrea Thompson.

Joanne Kenen: The Atlantic’s “Now Is Not the Time To Eat Bagged Lettuce,” by Nicholas Florko.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

- Politico’s “‘Rolling Thunder’: Inside Conservatives’ Strategy To Curb Abortion Pill Access,” by Alice Miranda Ollstein.

- The New York Times’ “Josh Hawley: Don’t Cut Medicaid,” by Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.).

- NPR’s “FDA Moves To Ban Fluoride Supplements for Kids, Removing a Key Tool for Dentists,” by Pien Huang.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: GOP Poised To Cut Billions in Health Benefits

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, May 15, at 9:30 a.m. As always, and particularly this week, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via videoconference by Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: Hello.

Rovner: Joanne Kenen of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Politico.

Joanne Kenen: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: And my KFF Health News colleague Julie Appleby.

Julie Appleby: Hi.

Rovner: No interview this week because so much news, so we will get straight to it. So, quiet week, huh? Just kidding. The House Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce committees completed all-nighter markups on their portions of President [Donald] Trump’s “one big, beautiful” reconciliation bill. And in fact, Ways and Means is officially calling it the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” in its summary of the measure.

We will start with Energy and Commerce, which after a 26-hour marathon, one hour short of the record it set in 2017, voted out its part of the bill Wednesday afternoon, including an estimated $715 billion in reductions to health programs, mostly Medicaid, over the next 10 years. Now, the final committee bill does not include the threatened cuts to the 90% match for the Affordable Care Act expansion population, nor does it include the per capita cap for that population.

Nonetheless, it would represent the biggest cut to Medicaid in the program’s 60-year history. Guys, tell us some of the things that it would do instead to get to that $715 billion amount.

Kenen: The 715 includes some ACA cuts as well. It’s not 100% Medicaid, but it’s largely Medicaid. The biggest one is the one that we knew was almost inevitable given the current Congress, which is work requirements. It is something the Republicans have wanted a long time. In the prior administration, a few states did pass them. Arkansas got going with them. The courts stopped it.

The Medicaid statute is pretty clear that it’s about health, not about health for working people. The courts today are different. If I had to guess, I would guess there will be a legal battle and that the courts are likely to uphold work requirements.

Rovner: We’ll talk more about work requirements in a minute. But what else is in the bill?

Kenen: There’s lots of extra layers of verification. Supposedly, it’s about fraud. We can get to the Kennedy testimony later, but there were some assertions that did not add up for me. The biggest thing is work requirements, and there’s other things that will make it harder to maintain coverage, that it’s not that tou’re getting kicked off, per se. And there are also some copays. There are some copays for the upper rank. There’s been a lot of information this week. And if I get any details wrong, because we’ve all had to absorb a lot in 48 hours, someone correct me. But my recollection was a $35 copay for certain treatments for the people who are on the higher end of the income.

Rovner: Right, meaning over 100% of poverty—

Kenen: Right.

Rovner: —but still under the level required to qualify for Medicaid.

Appleby: Right. It would require states actually to impose these cost sharings of up to $35 per service. Although they’re excluding some things like primary care, emergency stuff, that kind of thing, for people in that 100% of poverty to 138% of poverty, and there’s also an upper limit of 5% of the family’s income. But that’s a lot for people in that category.

Rovner: And we know, there is an enormous body of research that says when you put copays on services, people get fewer of them. And it’s not like people who are just scraping by have a lot of extra money to spend. So we know that one of the ways that they’ll save money is that people won’t get services, presumably needed services.

Kenen: Although the primary care exemption is important, because primary care, which also usually includes pediatricians, are considered primary care, can deal with a lot of diseases that you don’t always need to see a specialist. I’m not saying it’s a good idea. I’m just saying in terms of an incentive to get basic care, keeping primary care free is an important distinction.

Rovner: Well, I do want to talk a little bit about that work requirement, which Massachusetts Democratic Rep. Jake Auchincloss called not a work requirement but a paperwork requirement. Once more, for those who haven’t heard us explain this 100 times, it’s not just people who don’t work who lose coverage because of this. I see you nodding, Alice. Please explain this again.

Ollstein: Yes. So Democrats really hammered over the course of this 26-hour hearing that the only states that have made a foray in this direction so far, Arkansas and Georgia, have seen that these work requirements do not boost employment. They kick people off who should have been eligible because they can’t navigate, like you said, the paperwork. And so it was really striking, over this hearing, where — I watched from 8 a.m. Wednesday to 2 p.m. Wednesday — and during that whole time, every single amendment vote was party-line. Nobody crossed in either direction. So this was really a political exercise in Democrats because they were not able to convince Republicans to change or soften the bill at all. They really focused on branding it, branding it as punishing the poor and threatening their health care.

And so they were pointing to what happened in Arkansas, what happened in Georgia, where the work requirements really were successful in only that they cut people from the rolls and saved the states money, not successful in helping people find work or helping people get coverage. They also made an effort to brand the copays issue. I heard Democrats calling it a “sick tax.” We’ll see if that phrase sticks around throughout this process.

Rovner: So kind of in an interesting twist, the work requirements in the bill don’t become mandatory until the year 2029. That suggests to me that those who voted for this don’t really want it to take effect, but they do want to be able to count the savings to pay for other things in the bill. And then, cherry on top of the sundae, if Democrats want to repeal the work requirements later, they would have to find a way to pay for them, because the savings would get built into the budget baseline. Or is that just me being cynical because I’ve only had like five hours of sleep this week?

Kenen: Well, there are two important dates between now and 2029. One is the 2026 off-year elections, the House elections and some Senate, and then 2028 is the presidential. So there’s several things that have changed politically about Medicaid in recent years, which we can talk to and which I’ve written about quite extensively. One of them is that a lot of people who are Trump’s base are now on Medicaid and particularly that expansion population, and nobody likes having their health care taken away from them, particularly if it’s free or very, very heavily subsidized in the lower ranks of the exchanges.

So if you’re going to kick your own voters off of their health care, you’re probably more likely to want to do it after they voted for you again. It is not uniquely cynical. We have seen both parties do similar things over the years, either for budgetary game-playing or for political things. It’s quite notable that this goes into effect in 2029.

Ollstein: It’s just interesting that this is getting criticized from both sides. So Democrats are upset that Republicans want to reap the nominal savings but not have to look like the bad guy. And conservative Republicans are upset that this doesn’t kick in sooner, because they want stricter work requirements even sooner to cut the program even more. So it’s pleasing few.

Rovner: Well, as Joanne alluded to, it’s not just Medicaid. This bill is also a bit of a stealth assault on the Affordable Care Act, too. Right, Julie? We haven’t talked about it a lot, but this administration seems to be working very hard to make the ACA a lot less effective. And the combination of reductions in Medicaid and changes to the ACA will mean lots more people will be uninsured if this bill becomes law in its current form. Yes?

Appleby: There are a lot of moving parts to this. So yeah, let’s back up just briefly and look at March, when the Trump administration did propose their first major rule affecting the Affordable Care Act, and it’s called the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Marketplace Integrity … it’s a long-name rule. Anyway, it does a bunch of things. For one, it shortens the open enrollment period by about a month. So open enrollment would end on Dec. 15. And notably, this would apply to all states that run their own state-based marketplaces, as well as the federal marketplace. So there’s 16 plus D.C. that do that. So they would all also be tied to this. So that’s one of the things that the rule would do if it’s finalized in its form.

It would also end a special enrollment period that allows low-income people to essentially enroll anytime during the year. And people who are automatically reenrolled in a zero-premium plan would instead be charged a $5 premium for reenrollment in that same plan until they confirm their eligibility. Now, the Trump administration says that a lot of these rules are in part to try to combat what they say is fraud and waste, and they point to situations where people are being enrolled without their permission or switched to different plans, generally these zero-premium plans, by unscrupulous brokers who are trying to get commissions.

We’ve written a lot about that over the past year. So they’re saying that, Oh, we need to do this so that people know they’ve been enrolled. The special enrollment period for low-income people they thought was part of that. That’s disputed by a number of places. And some of the states have pushed back on this, too, and said, Hey, we don’t have this problem with fraud, so why would this now apply to us? Why would the special enrollment period, the shortened enrollment period, etc., etc.?

So those are things in the proposed rule. And the proposed rule acknowledges that it would reduce enrollment by about up to 2 million people in 2026, with coverage losses concentrated in a bunch of states like Alabama, Florida, Georgia, etc. So that’s the proposed rule. And then if you look at the House bill, like, for example, Energy and Commerce, these would codify some of those proposals from that ACA rule. So it would make it harder for a future president to change the rule and that kind of thing.

So those things that are codified would be — there’d be more hoops to jump through to verify income, for one thing. That special enrollment period based on income would be barred, and the shorter enrollment period would be in it. And if this goes through, these changes are set to go into effect next year. So a lot of insurers and states would have to scramble to try to get this put in place by then. So that’s just a short thing about what some of the ACA effects would be.

Rovner: So, it feels like there’s kind of a theme here that’s going to make it harder for people to get on and stay on both the ACA and Medicaid. Is that sort of a fair way to describe this?

Appleby: Yeah, that’s fair. In the House bills, there are also a lot of things that would bar automatic reenrollment, which a lot of people rely on. People just don’t go back in and sign up for their coverage. They’re automatically reenrolled. The bills differ a little bit. The harshest one would require everybody to sort of verify their income before they can reenroll. There would be a lot more of that. So it would essentially bar reenrollment. And we haven’t even talked about the enhanced tax credits, because that’s also sort of fitting here.

Rovner: Which was my, yes, my next question. So there’s been a lot of fighting this week about how many people would lose coverage as a result of this bill, and a lot of it is sort of philosophical fighting. We don’t have final CBO [Congressional Budget Office] numbers yet. We may not have them for another week, I am told. But what we do know is one of the things this bill could do but doesn’t do is re-up those additional subsidies that were installed during the Biden administration, during covid, that basically effectively doubled the number of people who enrolled under the marketplaces, right?

Appleby: It certainly added a lot. Most people who get a subsidy are benefiting from the enhanced subsidies. And remember, these sort of expanded at the lower end and it cut off that cliff at 400% of the poverty level that used to exist where you wouldn’t get a subsidy if you made more than that. So it smoothed all that out. So a lot of people are getting these extra subsidies.

And a lot of the data I’ve seen have said — I’m looking at an Oliver Wyman report earlier — something like, if these enhanced subsidies are allowed to expire at the end of this year, which they’re poised to do unless Congress acts, that, on average, premiums would go up by about 90%. That will be enough to cause a lot of people not to reenroll. So that’s where we’ve seen some of these estimates of I think it’s around 5 million people may not reenroll as a result of that over time.

That’s a pretty big number. But like you said, there’s a lot of numbers in the mix, but the enhanced premium subsidies do cost taxpayers. It’s not inexpensive. So if they’re looking for savings, which they are, Congress may decide not to extend them. But at the same time, many people and in a lot of states that are dominated by the GOP and others, people are getting these subsidies, and it would suddenly be a huge hit to many people to have a 90% increase in their premiums, for example.

Rovner: Yeah, as Joanne said. Which you’re about to say again, right? These are Republican voters now, right?

Kenen: I think that’s more mixed, the upper income within the ACA. We’ve expected that to go away, because there’s a difference between Congress having to yank something away versus something in the law that expires and they have to proactively renew it. We have always anticipated that enhanced subsidies would decline this year. But I just sort of want to point out, during the first Trump administration, without all this coverage, the uninsurance rate rose in the country.

And that even before ’29, there are all sorts of things, with shortened enrollment periods, how much outreach they do, there’s lots of things even before 2029 that we can expect a fairly significant erosion of health coverage. Not to what it was in pre-ACA levels — it’s not going to be that extreme, and not all the benefits that those of us with employer-sponsored insurance also get, some things through the ACA.

So this is not repeal — it’s damage. And it’s more damage than they did in the first Trump administration. All of us would be extremely surprised if there was not a significant drop in the number of insured Americans one, two years from now.

Rovner: One of the ways conservatives hope to secure the votes for this bill in the House is a provision that would bar Planned Parenthood from the Medicaid program. This would certainly be popular in the House. But when it was in the Affordable Care Act repeal bill in 2017, the Senate parliamentarian ruled that it couldn’t be included in budget reconciliation, because it is not primarily budgetary. Alice, are House leaders just hoping no one will remember that?

Ollstein: If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Yes, I think so. And especially because we just got a new CBO estimate of what the budgetary impact of cutting these funds would be. And it’s, like they have found before, it does not save money. It actually costs the government money because people lose access to contraception and don’t have other sources that they can afford to obtain contraception. And it’s a lot more expensive to have a baby on Medicaid than to access contraception. So I think that also contributes to the parliamentarian problem.

Rovner: Yes. You can put stuff in reconciliation that costs money, but that was sort of not the intent here. Joanne, you wanted to say something.

Kenen: And we should point out that this is still at the committee level, right? Is it going to get through the House in this exact form? We can’t be sure yet. Is something going to get through the House at the end of the day? Yes. Yes. But is all of this going to get in? Is this the final draft? Probably not. You have moderates who are still, don’t like some of the things in here, and you have conservatives who think it doesn’t go far enough.

As we said at the beginning, as far as it does go, it does not go anywhere near as far as the initial, of some of the things that were being discussed, which really would have ended Medicaid as an entitlement. These are big changes. They’re not existential in the same way that a per capita cap or a block grant or blowing up the ACA expansion by changing the rates. There are things they could have done that were far more radical that they don’t have the votes for. And—

Rovner: But they still can only lose, what, three or four votes and get something through the House.

Kenen: Right. Right. Because Medicaid is actually quite popular, and people in both parties are covered by it. We still don’t know the pathway, what gets through the House at the end of the day. Something does, right? We all think that they will, somehow or other. Not necessarily by Memorial Day, right? But something at some point will get through the House, and we don’t know exactly what it looks like.

Rovner: For the record, I’m still shrugging. I think something gets—

Kenen: And it is a bigger question mark, you know?

Rovner: Which is my next question. What are the prospects for this bill in the Senate? Do we really believe that the very conservative Missouri Republican Josh Hawley would vote against this? He had a piece in The New York Times this week saying, “Don’t Cut Medicaid.”

Kenen: He’s been really consistent. Have we seen politicians do huge flip-flops in our years of covering Congress and politics? Yes. He’s really out there on this. It’s sort of hard to see how he just says, Whoops, I didn’t really mean it. But right now in terms of who’s out there in public, we don’t have a critical mass of people who’ve said they can’t vote for this. But we do know there are provisions in this very extensive bill that some people don’t like. It will go through changes in the Senate.

I don’t have a grasp and I don’t think any of us have a grasp on exactly what’s going to change. I think work requirements, depending on what bells and whistles are attached, could get through the Senate. There might be changes like making it a state option or redefining certain things with it. I think there probably are 51 votes for a work requirement of some type in the Senate.

That doesn’t mean the way this has been written survives. And there’s just — these are big cuts. And there’s also, remember, we’re only talking about the health stuff. There’s a lot. There’s energy. There’s all sorts of — this is a big bill. This is a big, historic bill. There’s lots and lots of hurdles. We all remember that the ACA repeal, it took several tries. It was really harder than expected. It finally got through the House, and it did die in the Senate. So this is not the last word. We don’t have to shut the podcast.

Rovner: Yes, long way to go. All right, moving on. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. testified before not one but two committees on Wednesday: the House labor, HHS Appropriations subcommittee in the morning and the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee in the afternoon. And shall we say it didn’t all go swimmingly. Right off the bat, this was the greeting he got from House Appropriations Committee ranking member Rosa DeLauro of Connecticut. DeLauro basically saying, Everything you’re doing is illegal.

Rep. Rosa DeLauro: Mr. Secretary, this administration is recklessly and unlawfully freezing and stealing congressionally appropriated funds from a wide swath of agencies, programs, and services across the government that serve the American people. And recall that this is a violation of the Constitution.

The power of the purse resides with the Congress. It’s Article 1, Section 9, Clause 7. Yourself and President Trump and Elon Musk are attacking health programs to pay for tax cuts for billionaires. And by promoting quackery, we are endangering the health of the American people with pseudoscience, fearmongering, and misinformation.

Rovner: If you want to hear more, we did a live recap of the hearings yesterday afternoon. You can find that on KFF’s YouTube page. But I want to know what you all took away from the hearings. Joanne, you watched most of them, right?

Kenen: I watched a lot of it. I did not watch every minute of both hearings, but I watched enough. And I thought that very first exchange with DeLauro was really striking because she kept saying, over and over and over again she kept saying: Congress appropriated this money. You don’t have the right to not spend it. And he kept saying, If you appropriate the money, I will spend it. And she said, We have appropriated the money, and you’re not spending it. And he said, If you appropriate the money …

And she explained. What a continuing wrestle. It was like this endless — well, it wasn’t endless, but it was repeated when she kept saying, We appropriated it, and he kept saying, Huh? And she actually said the first time sort of under her breath, but the mic picked it up, and then she said it again. She said, “Unbelievable.” She’s not known for understatement, but she said, “Unbelievable.” And then she said it again. “Unbelievable.” So that was sort of — the rest of the day was sort of there.

Rovner: Yeah. I personally found it refreshing that someone finally called out HHS, saying: You know, there was an appropriations bill that got signed by the president, and you are withholding this money. And this is our province. We get to decide how the money is spent. You don’t get to decide how the money is spent. The other big headline that came out of this hearing was when Kennedy said that, after being raked over the coals again about his vaccine comments, he said, Well, you shouldn’t be taking medical advice from me. And I’m like, isn’t that the job of the HHS secretary?