by Admin

Journalists Assess Health Impacts of Trump’s Megabill, Who Will Feel Them, and When

KFF Health News chief Washington correspondent Julie Rovner discussed how cuts to Medicaid in President Donald Trump’s megabill will affect Americans’ access to health care on NPR’s “Up First,” CNN’s “CNN This Morning” and WNYC’s “The Brian Lehrer Show” on July 2. Rovner also discussed U.S. […]

Pharmaceuticals

by Admin

How an Ontario tech company is looking to track the spread of dangerous diseases

With a worldwide pandemic, and now measles outbreaks, a new Ontario company is trying to make it easier for people to understand how diseases are spreading in their community.

Flu season

by Admin

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Supreme Court Upholds Bans on Gender-Affirming Care

The Host Julie Rovner KFF Health News @jrovner @julierovner.bsky.social Read Julie’s stories. Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the […]

Pharmaceuticals

Journalists Assess Health Impacts of Trump’s Megabill, Who Will Feel Them, and When

by Admin

KFF Health News chief Washington correspondent Julie Rovner discussed how cuts to Medicaid in President Donald Trump’s megabill will affect Americans’ access to health care on NPR’s “Up First,” CNN’s “CNN This Morning” and WNYC’s “The Brian Lehrer Show” on July 2. Rovner also discussed U.S. […]

PharmaceuticalsKFF Health News chief Washington correspondent Julie Rovner discussed how cuts to Medicaid in President Donald Trump’s megabill will affect Americans’ access to health care on NPR’s “Up First,” CNN’s “CNN This Morning” and WNYC’s “The Brian Lehrer Show” on July 2. Rovner also discussed U.S. domestic and global vaccine policy on WAMU’s “1A” on July 1.

- Click here to hear Rovner on “Up First”

- Click here to watch Rovner on “CNN This Morning”

- Click here to hear Rovner on “The Brian Lehrer Show”

- Click here to hear Rovner on “1A”

- Read “Republican Megabill Will Mean Higher Health Costs for Many Americans,” by Phil Galewitz, Julie Appleby, Renuka Rayasam, and Bernard J. Wolfson

Céline Gounder, KFF Health News’ editor-at-large for public health, discussed a new study that found a link between a common type of hormone therapy and higher rates of breast cancer on CBS’ “CBS Mornings” on July 2. Gounder also discussed a breakthrough drug for HIV prevention on CBS’ “CBS Mornings Plus” on July 1.

- Click here to watch Gounder discuss the hormone therapy study on “CBS Mornings”

- Click here to watch Gounder discuss the new HIV prevention drug on “CBS Mornings Plus”

KFF Health News chief rural correspondent Sarah Jane Tribble discussed how Medicaid cuts in President Trump’s megabill could strain rural hospitals on CNN’s “CNN News Central” and on NPR’s “All Things Considered” on July 2 and July 1, respectively.

- Click here to watch Tribble on “CNN News Central”

- Click here to hear Tribble on “All Things Considered”

- Read “Republican Megabill Will Mean Higher Health Costs for Many Americans,” by Phil Galewitz, Julie Appleby, Renuka Rayasam, and Bernard J. Wolfson

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

How an Ontario tech company is looking to track the spread of dangerous diseases

With a worldwide pandemic, and now measles outbreaks, a new Ontario company is trying to make it easier for people to understand how diseases are spreading in their community.

Flu seasonWith a worldwide pandemic, and now measles outbreaks, a new Ontario company is trying to make it easier for people to understand how diseases are spreading in their community.

by Admin

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Supreme Court Upholds Bans on Gender-Affirming Care

The Host Julie Rovner KFF Health News @jrovner @julierovner.bsky.social Read Julie’s stories. Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the […]

PharmaceuticalsThe Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

The Supreme Court this week ruled in favor of Tennessee’s law banning most gender-affirming care for minors — a law similar to those in two dozen other states.

Meanwhile, the Senate is still hoping to complete work on its version of President Donald Trump’s huge budget reconciliation bill before the July Fourth break. But deeper cuts to the Medicaid program than those included in the House-passed bill could prove difficult to swallow for moderate senators.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Victoria Knight of Axios, Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico, and Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Panelists

Victoria Knight

Axios

Alice Miranda Ollstein

Politico

Sandhya Raman

CQ Roll Call

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- The Supreme Court’s ruling on gender-affirming care for transgender minors was relatively limited in its scope. The majority did not address the broader question about whether transgender individuals are protected under federal anti-discrimination laws and, as with the court’s decision overturning the constitutional right to an abortion, left states the power to determine what care trans youths may receive.

- The Senate GOP unveiled its version of the budget reconciliation bill this week. Defying expectations that senators would soften the bill’s impact on health care, the proposal would make deeper cuts to Medicaid, largely at the expense of hospitals and other providers. Republican senators say those cuts would allow them more flexibility to renew and extend many of Trump’s tax cuts.

- The Medicare trustees are out this week with a new forecast for the program that covers primarily those over age 65, predicting insolvency by 2033 — even sooner than expected. There was bipartisan support for including a crackdown on a provider practice known as upcoding in the reconciliation bill, a move that could have saved a bundle in government spending. But no substantive cuts to Medicare spending ultimately made it into the legislation.

- With the third anniversary of the Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade approaching, the movement to end abortion has largely coalesced around one goal: stopping people from accessing the abortion pill mifepristone.

Plus, for “extra credit,” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: The New York Times’ “The Bureaucrat and the Billionaire: Inside DOGE’s Chaotic Takeover of Social Security,” by Alexandra Berzon, Nicholas Nehamas, and Tara Siegel Bernard.

Victoria Knight: The New York Times’ “They Asked an A.I. Chatbot Questions. The Answers Sent Them Spiraling,” by Kashmir Hill.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: Wired’s “What Tear Gas and Rubber Bullets Do to the Human Body,” by Emily Mullin.

Sandhya Raman: North Carolina Health News and The Charlotte Ledger’s “Ambulance Companies Collect Millions by Seizing Wages, State Tax Refunds,” by Michelle Crouch.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

- KFF’s “KFF Health Tracking Poll: Views of the One Big Beautiful Bill,” by Ashley Kirzinger, Lunna Lopes, Marley Presiado, Julian Montalvo III, and Mollyann Brodie.

- The Associated Press’ “Trump Administration Gives Personal Data of Immigrant Medicaid Enrollees to Deportation Officials,” by Kimberly Kindy and Amanda Seitz.

- The Guardian’s “VA Hospitals Remove Politics and Marital Status From Guidelines Protecting Patients From Discrimination,” by Aaron Glantz.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Supreme Court Upholds Bans on Gender-Affirming Care

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Friday, June 20, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via videoconference by Alice Miranda Ollstein of Politico.

Alice Miranda Ollstein: Hello.

Rovner: Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Sandhya Raman: Good morning.

Rovner: And Victoria Knight of Axios News.

Victoria Knight: Hello, everyone.

Rovner: No interview this week but more than enough news to make up for it, so we will go right to it. It is June. That means it is time for the Supreme Court to release its biggest opinions of the term. On Wednesday, the justices upheld Tennessee’s law banning gender-affirming medical care for trans minors. And presumably that means similar laws in two dozen other states can stand as well. Alice, what does this mean in real-world terms?

Ollstein: So, this is a blow to people’s ability to access gender-affirming care as minors, even if their parents support them transitioning. But it’s not necessarily as restrictive a ruling as it could have been. The court could have gone farther. And so supporters of access to gender-affirming care see a silver lining in that the court didn’t go far enough to rule that all laws discriminating against transgender people are fine and constitutional. A few justices more or less said that in their separate opinions, but the majority opinion just stuck with upholding this law, basically saying that it doesn’t discriminate based on gender or transgender status.

Rovner: Which feels a little odd.

Ollstein: Yes. So, obviously, many people have said, How can you say that laws that only apply to transgender people are not discriminatory? So, been some back-and-forth about that. But the majority opinion said, Well, we don’t have to reach this far and decide right now if laws that discriminate against transgender people are constitutional, because this law doesn’t. They said it discriminates based on diagnosis — so anyone of any gender who has the diagnosis of gender dysphoria for medications, hormones, that’s not a gender discrimination. But obviously the only people who do have those diagnoses are transgender, and so it was a logic that the dissenters, the three progressive dissenters, really ripped into.

Rovner: And just to be clear, we’ve heard about, there are a lot of laws that ban sort of not-reversible types of treatments for minors, but you could take hormones or puberty blockers. This Tennessee law covers basically everything for trans care, right?

Ollstein: That’s right, but only the piece about medications was challenged up to the Supreme Court, not the procedures and surgeries, which are much more rare for minors anyways. But it is important to note that some of the conservatives on the court said they would’ve gone further, and they basically said, This law does discriminate against transgender kids, and that is fine with us. And they said the court should have gone further and made that additional argument, which they did not at this time.

Rovner: Well, I’m sure the court will get another chance sometime in the future. While we’re on the subject of gender-affirming care in the courts, in Texas on Wednesday, conservative federal district judge Matthew Kacsmaryk — that’s the same judge who unsuccessfully tried to repeal the FDA’s [Food and Drug Administration’s] approval of the abortion pill a couple of years ago — has now ruled that the Biden administration’s expansion of the HIPAA [Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act] medical privacy rules to protect records on abortion and gender-affirming care from being used for fishing expeditions by conservative prosecutors was an overreach, and he slapped a nationwide injunction on those rules. What could this mean if it’s ultimately upheld?

Ollstein: I kind of see this in some ways like the Trump administration getting rid of the EMTALA [Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act] guidance, where the underlying law is still there. This is sort of an interpretation and a guidance that was put out on top of it, saying, We interpret HIPAA, which has been around a long time, to apply in these contexts, because we’re in this brave new world where we don’t have Roe v. Wade anymore and states are seeking records from other states to try to prosecute people for circumventing abortion bans. And so, that wasn’t written into statute before, because that never happened before.

And so the Biden administration was attempting to respond to things like that by putting out this rule, which has now been blocked nationwide. I’m sure litigation will continue. There are also efforts in the courts to challenge HIPAA more broadly. And so, I would be interested in tracking how this plays into that.

Rovner: Yeah. There’s plenty of efforts sort of on this front. And certainly, with the advent of AI [artificial intelligence], I think that medical privacy is going to play a bigger role sort of as we go forward. All right. Moving on. While the Supreme Court is preparing to wrap up for the term, Congress is just getting revved up. Next up for the Senate is the budget reconciliation, quote, “Big Beautiful Bill,” with most of President [Donald] Trump’s agenda in it. This week, the Senate Finance Committee unveiled its changes to the House-passed bill, and rather than easing back on the Medicaid cuts, as many had expected in a chamber where just a few moderates can tank the entire bill, the Finance version makes the cuts even larger. Do we have any idea what’s going on here?

Knight: Well, I think mostly they want to give themselves more flexibility in order to pursue some of the tax policies that President Trump really wants. And so they need more savings, basically, to be able to do that and be able to do it for a longer amount of years. And so that’s kind of what I’ve heard, is they wanted to give themselves more room to play around with the policy, see what fits where. But a lot of people were surprised because the Senate is usually more moderate on things, but in this case I think it’s partially because they specifically looked at a provision called provider taxes. It’s a way that states can help fund their Medicaid programs, and so it’s a tax levied on providers. So I think they see that as maybe — it could still affect people’s benefits, but it’s aimed at providers — and so maybe that’s part of it as well.

Rovner: Well, of course aiming at providers is not doing them very much good, because hospitals are basically freaking out over this. Now there is talk of creating a rural hospital slush fund to maybe try to quell some of the complaints from hospitals and make some of those moderates feel better about voting for a bill that the Congressional Budget Office still says takes health insurance and food aid from the poor to give tax cuts to the rich. But if the Senate makes a slush fund big enough to really protect those hospitals, wouldn’t that just eliminate the Medicaid savings that they need to pay for those tax cuts, Victoria? That’s what you were just saying. That’s why they made the Medicaid cuts bigger.

Knight: Yeah. I think there’s quite a few solutions that people are throwing around and proposing. Yeah, but, exactly. Depending on if they do a provider relief fund, yeah, then the savings may need to go to that. I’ve also heard — I was talking to senators last week, and some of them were like, I’d rather just go back to the House’s version. So the House’s version of the bill put a freeze on states’ ability to raise the provider tax, but the Senate version incrementally lowers the amount of provider tax they can levy over years. The House just freezes it and doesn’t allow new ones to go higher. Some senators are like: Actually, can we just do that, go back to that? And we could live with that.

Even Sen. Josh Hawley, who has been one of the biggest vocal voices on concern for rural hospitals and concern for Medicaid cuts, he told me, Freeze would be OK with me. And so, I don’t know. I could see them maybe doing that, but we’ll see. There’s probably more negotiations going on over the weekend, and they’re also going to start the “Byrd bath” procedure, which basically determines whether provisions in the bill are related to the budget or not and can stay in the bill. And so, there’s actually gender-affirming care and abortion provisions in the bill that may get thrown out because of that. So—

Rovner: Yeah, this is just for those who don’t follow reconciliation the way we do, the “Byrd bath,” named for the former Sen. [Robert] Byrd, who put this rule in that said, Look, if you’re going to do this big budget bill with only 50 votes, it’s got to be related to the budget. So basically, the parliamentarian makes those determinations. And what we call the “Byrd bath” is when those on both sides of a provision that’s controversial go to the parliamentarian in advance and make their case. And the parliamentarian basically tells them in private what she’s going to do — like, This can stay in, or, This will have to go out. If the parliamentarian rules it has to go out, then it needs to overcome a budget point of order that needs 60 votes. So basically, that’s why stuff gets thrown out, unless they think it’s popular enough that it could get 60 votes. And sorry, that’s my little civics lesson for the day. Finish what you were saying, Victoria.

Knight: No, that was a perfect explanation. Thank you. But I was just saying, yeah, I think that there are still some negotiations going on for the Medicaid stuff. And where also, you have to remember, this has to go back to the House. And so it passed the House with the provider tax freeze, and that still required negotiations with some of the more moderate members of House Republicans. And some of them started expressing their concern about the Senate going further. And so they still need to — it has to go back through the House again, so they need to make these Senate moderates happy and House moderates happy. There’s also the fiscal conservatives that want deeper cuts. So there’s a lot of people within the caucus that they need to strike a balance. And so, I don’t know if this will be the final way the bill looks yet.

Rovner: Although, I think I say this every week, we have all of these Republicans saying: I won’t vote for this bill. I won’t vote for this bill. And then they inevitably turn around and vote for this bill. Do we believe that any of these people really would tank this bill?

Knight: That’s a great point. Yeah. Sandhya, go ahead.

Raman: There are at least a couple that I don’t think, anything that we do, they’re not going to change their mind. There is no courting of Rep. [Thomas] Massie in the House, because he’s not going to vote for it. I feel like in the Senate it’s going to be really hard to get Rand Paul on board, just because he does not want to raise the deficit. I think the others, it’s a little bit more squishy, depends kind of what the parliamentarian pulls out. And I guess also one thing I’m thinking about is if the things they pull out are big cost-savers and they have to go back to the drawing board to generate more savings. We’ve only had a few of the things that they’ve advised on so far, but it’s not health, and we still need to see — health are the big points. So, I think—

Rovner: Well, they haven’t started the “Byrd bath” on the Finance provisions—

Raman: Yes, or—

Rovner: —which is where all the health stuff is.

Raman: Yeah.

Knight: But that is supposed to be over the weekend. It’s supposed to start over the weekend.

Raman: Yes.

Rovner: Right.

Raman: Yeah. So, I think, depending on that, we will see. Historically, we have had people kind of go back and forth. And even with the House, there were people that voted for it that then now said, Well, I actually don’t support that anymore. So I think just going back to just what the House said might not be the solution, either. They have to find some sort of in-between before their July Fourth deadline.

Rovner: I was just going to say, so does this thing happen before July Fourth? I noticed that that Susie Wiles, the White House chief of staff said: Continue. It needs to be on the president’s desk by July Fourth. Which seems pretty nigh impossible. But I could see it getting through the Senate by July Fourth. I’m seeing some nods. Is that still the goal?

Knight: Yeah. I think that’s the goal. That’s what Senate Majority Leader [John] Thune has been telling people. He wants to try to pass it by mid-, or I think start the process by, midweek. And then it’s going to have to go through a “vote-a-rama.” So Democrats will be able to offer a ton of amendments. It’ll probably go through the night, and that’ll last a while. And so, I saw some estimate, maybe it’ll get passed next weekend through the Senate, but that’s probably if everything goes as it’s supposed to go. So, something could mess that up.

But, yeah, I think the factor here that has — I think everyone’s kind of been like: They’re not going to be able to do it. They’re not going to be able to do it. With the House, especially — the House is so rowdy. But then, when Trump calls people and tells them to vote for it, they do it. There’s a few, yeah, like Rand Paul and Massie — they’re basically the only ones that will not vote when Trump tells them to. But other than that — so if he wants it done, I do think he can help push to get it done.

Rovner: Yeah. I noticed one change, as I was going through, in the Senate bill from the House bill is that they would raise the debt ceiling to $5 trillion. It’s like, that’s a pretty big number. Yeah. I’m thinking that alone is what says Rand Paul is a no. Before we move on, one more thing I feel like we can’t repeat enough: This bill doesn’t just cut Medicaid spending. It also takes aim at the Affordable Care Act and even Medicare. And a bunch of new polls this week show that even Republicans aren’t super excited about this bill. Are Republican members of Congress going to notice this at some point? Yeah, the president is popular, but this bill certainly isn’t.

Raman: When you look at some of the town halls that they’ve had — or tried to have — over the last couple months and then scaled back because there was a lot of pushback directly on this, the Medicaid provisions, they have to be aware. But I think if you look at that polling, if you look at the people that identify as MAGA within Republicans, it’s popular for them. It’s just more broadly less popular. So I think that’s part of it, but—

Ollstein: I think that people are very opposed to the policies in the bill, but I also think people are very overwhelmed and distracted right now. There’s a lot going on, and so I’m not sure there will be the same national focus on this the way there was in 2017 when people really rallied in huge ways to protect the Affordable Care Act and push Congress not to overturn it. And so I think maybe that could be a factor in that outrage not manifesting as much. I also think that’s a reason they’re trying to do this quickly, that July Fourth deadline, before those protest movements have an opportunity to sort of organize and coalesce.

Just real quickly on the rural hospital slush fund, I saw some smart people comparing it to a throwback, the high-risk pools model, in that unless you pour a ton of funding into it, it’s not going to solve the problem. And if you pour a ton of funding into it, you don’t have the savings that created the problem in the first place, the cuts. And all that is to say also, how do we define rural? A lot of suburban and urban hospitals are also really struggling currently and would be subject to close. And so now you get into the pitting members and districts against each other, because some people’s hospitals might be saved and others might be left out in the cold. And so I just think it’s going to be messy going forward.

Rovner: I spent a good part of the late ’80s and early ’90s pulling out of bills little tiny provisions that would get tucked in to reclassify hospitals as rural so they could qualify, because there are already a lot of programs that give more money to rural hospitals to keep them open. Sorry, Victoria, we should move on, but you wanted to say one more thing?

Knight: Oh, yeah. No. I was just going to say, going back to the unpopularity of the bill based on polling, and I think that we’ll see at least Democrats — if Republicans get this done and they have the work requirements and the other cuts to Medicaid in the bill, cuts to ACA, no renewal of premium tax credits — I think Democrats will really try to make the midterms about this, right? We already are seeing them messaging about it really hardcore, and obviously the Democrats are trying to find their way right now post-[Joe] Biden, post-[Kamala] Harris. So I think they’ll at least try to make this bill the thing and see if it’s unpopular with the general public, what Republicans did with health care on this. So we’ll see if that works for them, but I think they’re going to try.

Rovner: Yeah, I think you’re right. Well, speaking of Medicare, we got the annual trustees report this week, and the insolvency date for Medicare’s Hospital Insurance Trust Fund has moved up to 2033. That’s three years sooner than predicted last year. Yet there’s nothing in the budget reconciliation bill that would address that, not even a potentially bipartisan effort to go after upcoding in Medicare Advantage that we thought the Finance Committee might do, that would save money for Medicare that insurers are basically overcharging the government for. What happened to the idea of going after Medicare Advantage overpayments?

Knight: My general vibe I got from asking senators was that Trump said, We’re not touching Medicare in this bill. He did not want that to happen. And I think, again, maybe potentially thinking about the midterms, just the messaging on that, touching Medicare, it kind of always goes where they don’t want to touch Medicare, because it’s older people, but Medicaid is OK, even though it’s poor people.

Rovner: And older people.

Ollstein: And they are touching Medicare in the bill anyway.

Rovner: Thank you. I know. I think that’s the part that makes my head swim. It’s like, really? There are several things that actually touch Medicare in this bill, but the thing that they could probably save a good chunk of money on and that both parties agree on is the thing that they’re not doing.

Knight: Exactly. It was very bipartisan.

Rovner: Yes. It was very bipartisan, and it’s not there. All right. Moving on. Elon Musk has gone back to watching his SpaceX rockets blow up on the launchpad, which feels like a fitting metaphor for what’s been left behind at the Department of Health and Human Services following some of the DOGE [Department of Government Efficiency] cuts. On Monday, a federal judge in Massachusetts ruled that billions of dollars in cuts to about 800 NIH [National Institutes of Health] research grants due to DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] were, quote, “arbitrary and capricious” and wrote, quote, “I’ve never seen government racial discrimination like this.” And mind you, this was a judge who was appointed by [President] Ronald Reagan. So what happens now? It’s been months since these grants were terminated, and even though the judge has ordered the funding restored, this obviously isn’t the last word, and one would expect the administration’s going to appeal, right? So these people are just supposed to hang out and wait to see if their research gets to continue?

Raman: This has been a big thing that has come up in all of the appropriations hearings we’ve had so far this year, that even though the gist of that is to look forward at the next year’s appropriations, it’s been a big topic of just: There is funding that we as Congress have already appropriated for this. Why isn’t it getting distributed? So I think that will definitely be something that they push back up on the next ones of those. Some of the different senators have said that they’ve been looking into it and how it’s been affecting their districts. So I would say that. But I think the White House in response to that called the decision political, which I thought was interesting given, like you said, it was a Reagan appointee that said this. So it’ll definitely be something that I think will be appealed and be a major issue.

Ollstein: Yeah, and the folks I’ve talked to who’ve been impacted by this stress that you can’t flip funding on and off like a switch and expect research to continue just fine. Once things are halted, they’re halted. And in a lot of cases, it is irreversible. Samples are thrown out. People are laid off. Labs are shut down. Even if there’s a ruling that reverses the policy, that often comes too late to make a difference. And at the same time, people are not waiting around to see how this back-and-forth plays out. People are getting actively recruited by universities and other countries saying: Hey, we’re not going to defund you suddenly. Come here. And they’re moving to the private sector. And so I think this is really going to have a long impact no matter what happens, a long tail.

Rovner: And yet we got another reminder this week of the major advances that federally funded research can produce, with the FDA approval of a twice-a-year shot that can basically prevent HIV infection. Will this be able to make up maybe for the huge cuts to HIV programs that this administration is making?

Raman: It’s only one drug, and we have to see what the price is, what cost—

Rovner: So far the price is huge. I think I saw it was going to be like $14,000 a shot.

Raman: Which means that something like PrEP [pre-exposure prophylaxis] is still going to be a lot more affordable for different groups, for states, for relief efforts. So I think that it’s a good step on the research front, but until the price comes down, the other tools in the toolbox are going to be a lot more feasible to do.

Rovner: Yeah. So much for President Trump’s goal to end HIV. So very first-term. All right. Well, turning to abortion, it’s been almost exactly three years since the Supreme Court overturned the nationwide right to abortion in the Dobbs case. In that time we’ve seen abortion outlawed in nearly half the states but abortions overall rise due to the expanded use of abortion medication. We’ve seen doctors leaving states with bans, for fear of not being able to provide needed care for patients with pregnancy complications. And we’ve seen graduating medical students avoiding taking residencies in those states for the same reason. Alice, what’s the next front in the battle over abortion in the U.S.?

Ollstein: It’s been one of the main fronts, even before Dobbs, but it’s just all about the pills right now. That’s really where all of the attention is. So whether that’s efforts ongoing in the courts back before our friend Kacsmaryk to try to challenge the FDA’s policies around the pills and impose restrictions nationwide, there’s efforts at the state level. There’s agitation for Congress to do something, although I think that’s the least likely option. I think it’s much more likely that it’s going to come from agency regulation or from the courts or from states. So I would put Congress last on the list of actors here. But I think that’s really it. And I think we’re also seeing the same pattern that we see in gender-affirming care battles, where there’s a lot of focus on what minors can access, what children can access, and that then expands to be a policy targeting people of any age.

So I think it’s going to be a factor. One thing I think is going to slow down significantly are these ballot initiatives in the states. There’s only a tiny handful of states left that haven’t done it yet and have the ability to do it. A lot of states, it’s not even an option. So I would look at Idaho for next year, and Nevada. But I don’t think you’re going to see the same storm of them that you have seen the last few years. And part of that is, like I said, there’s just fewer left that have the ability. But also some people have soured on that as a tactic and feel that they haven’t gotten the bang for the buck, because those campaigns are extremely expensive, extremely resource-intensive. And there’s been frustration that, in Missouri, for instance, it’s sort of been — the will of the people has sort of been overturned by the state government, and that’s being attempted in other states as well. And so it has seemed to people like a very expensive and not reliable protection, although I’m not sure in some states what the other option would even be.

Rovner: Of course the one thing that is happening on Capitol Hill is that the House Judiciary Committee last week voted to repeal the 1994 Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act, or FACE. Now this law doesn’t just protect abortion clinics but also anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers. This feels like maybe not the best timing for this sort of thing, especially in light of the shootings of lawmakers in Minnesota last weekend, where the shooter reportedly had in his car a list of abortion providers and abortion rights supporters. Might that slow down this FACE repeal effort?

Ollstein: I think it already was going to be an uphill battle in the Senate and even maybe passing the full House, because even some conservatives say, Well, I don’t know if we should get rid of the FACE Act, because the FACE Act also applies to conservative crisis pregnancy centers. And lest we forget, only a few short weeks ago, an IVF [in vitro fertilization] clinic was bombed, and it would’ve applied in that situation, too. And so some conservatives are divided on whether or not to get rid of the FACE Act. And so I don’t know where it is going forward, but I think these recent instances of violence certainly are not helping the efforts, and the Trump administration has already said they’re not really going to enforce FACE against people who protest outside of abortion clinics. And so that takes some of the heat off of the conservatives who want to get rid of it. Of course, they say it shouldn’t be left for a future administration to enforce, as the Biden administration did.

Raman: It also applies to churches, which I think if you are deeply religious that could also be a point of contention for you. But, yeah, I think just also with so much else going on and the fact that they’ve kind of slowed down on taking some of these things up for the whole chamber to vote on outside of in January, I don’t really see it coming up in the immediate future for a vote.

Rovner: Well, at the same time, there are efforts in the other direction, although the progress on that front seems to be happening in other countries. The British Parliament this week voted to decriminalize basically all abortions in England and Wales, changing an 1861 law. And here on this side of the Atlantic, four states are petitioning the FDA to lift the remaining restrictions on the abortion pill, mifepristone, even as — Alice, as you mentioned — abortion foes argue for its approval to be revoked. You said that the abortion rights groups are shying away from these ballot measures even if they could do it. What is going to be their focus?

Ollstein: Yeah, and I wouldn’t say they’re shying away from it. I’ve just heard a more divided view as a tactic and whether it’s worth it or not. But I do think that these court battles are really going to be where a lot is decided. That’s how we got to where we are now in the first place. And so the effort to get rid of the remaining restrictions on the abortion pill, the sort of back-and-forth tug here, that’s also been going on for years and years, and so I think we’re going to see that continue as well. And I think there’s also going to be, parallel to that, a sort of PR war. And I think we saw that recently with anti-abortion groups putting out their own not-peer-reviewed research to sort of bolster their argument that abortion pills are dangerous. And so I think you’re going to see more things like that attempting to — as one effort goes on in court, another effort in parallel in the court of public opinion to make people view abortion pills as something to fear and to want to restrict.

Rovner: All right. Well, finally this week, a couple of stories that just kind of jumped out at me. First, the AP [Associated Press] is reporting that Medicaid officials, over the objections of some at the agency, have turned over to the Department of Homeland Security personal data on millions of Medicaid beneficiaries, including those in states that allow noncitizens to enroll even if they’re not eligible for federal matching funds, so states that use their own money to provide insurance to these people. That of course raises the prospect of DHS using that information to track down and deport said individuals. But on a broader level, one of the reasons Medicaid has been expanded for emergencies and in some cases for noncitizens is because those people live here and they get sick. And not only should they be able to get medical care because, you know, humanity, but also because they may get communicable diseases that they can spread to their citizen neighbors and co-workers. Is this sort of the classic case of cutting off your nose despite your face?

Ollstein: I think we saw very clearly during covid and during mpox and measles, yes. What impacts one part of the population impacts the whole population, and we’re already seeing that these immigration crackdowns are deterring people, even people who are legally eligible for benefits and services staying away from that. We saw that during Trump’s first term with the public charge rule that led to people disenrolling in health programs and avoiding services. And that effect continued. There’s research out of UCLA showing that effect continued even after the Biden administration got rid of the policy. And so fear and the chilling effect can really linger and have an impact and deter people who are citizens, are legal immigrants, from using that as well. It’s a widespread impact.

Rovner: And of course, now we see the Trump administration revoking the status of people who came here legally and basically declaring them illegal after the fact. Some of this chilling effect is reasonable for people to assume. Like the research being cut off, even if these things are ultimately reversed, there’s a lot of — depends whether you consider it damage or not — but a lot of the stuff is going to be hard. You’re not going to be able to just resume, pick up from where you were.

Ollstein: And one concern I’ve been hearing particularly is around management of bird flu, since a lot of legal and undocumented workers work in agriculture and have a higher likelihood of being exposed. And so if they’re deterred from seeking testing, seeking treatment, that could really be dangerous for the whole population.

Rovner: Yeah. It is all about health. It is always all about health. All right. Well, the last story this week is from The Guardian, and it’s called “VA Hospitals Remove Politics and Marital Status From Guidelines Protecting Patients From Discrimination.” And it’s yet another example of how purging DEI language can at least theoretically get you in trouble. It’s not clear if VA [Department of Veterans Affairs] personnel can now actually discriminate against people because of their political party or because they’re married or not married. The administration says other safeguards are still in place, but it is another example of how sweeping changes can shake people’s confidence in government programs. I imagine the idea here is to make people worried about discrimination and therefore less likely to seek care, right?

Raman: It’s also just so unusual. I have not heard of anything like this before in anything that we’ve been reporting, where your political party is pulled into this. It just seems so out of the realm of what a provider would need to know about you to give you care. And then I could see the chilling effect in the same way, where if someone might want to be active on some issue or share their views, they might be more reluctant to do so, because they know they have to get care. And if that could affect their ability to do so, if they would have to travel farther to a different VA hospital, even if they aren’t actually denying people because of this, that chilling effect is going to be something to watch.

Rovner: And this is, these are not sort of theoretical things. There was a case some years ago about a doctor, I think he was in Kentucky, who wouldn’t prescribe birth control to women who weren’t married. So there was reason for having these protections in there, even though they are not part of federal anti-discrimination law, which is what the Trump administration said. Why are these things in there? They’re not required, so we’re going to take them out. That’s basically what this fight is over. But it’s sort of an — I’m sure there are other places where this is happening. We just haven’t seen it yet.

All right, well, that is this week’s news. Now it’s time for our extra-credit segment. That’s where we each recognize the story we read this week we think you should read, too. Don’t worry if you miss it. We will put the links in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device. Victoria, why don’t you go first this week?

Knight: Sure thing. My extra credit, it’s from The New York Times. The title is, “They Asked an A.I. Chatbot Questions. The Answers Sent Them Spiraling,” by Kashmir Hill, who covers technology at The Times. I had seen screenshots of this article being shared on X a bunch last week, and I was like, “I need to read this.”

Basically it shows that different people who, they may be going through something, they may have a lot of stress, or they may already have a mental health condition, and they start messaging ChatGPT different things, then ChatGPT can kind of feed into their own delusions and their own misaligned thinking. That’s because that’s kind of how ChatGPT is built. It’s built to be, like, they call it in the story, like a sycophant. Is that how you say it? So it kind of is supposed to react positively to what you’re saying and kind of reinforce what you’re saying. And so if you’re feeding it delusions, it will feed delusions back. And so it was really scary because real-life people were impacted by this. There was one individual who thought he was talking to — had found an entity inside of ChatGPT named Juliet, and then he thought that OpenAI killed her. And so then he ended up basically being killed by police that came to his house. It was just — yeah, there was a lot of real-life effects from talking to ChatGPT and having your own delusions reinforced. So, and so it was just an effect of ChatGPT on real-life people that I don’t know if we’ve seen illustrated in a news story yet. And so it was very illuminating, yeah.

Rovner: Yeah. Not scary much. Sandhya.

Raman: My extra credit was “Ambulance Companies Collect Millions by Seizing Wages, State Tax Refunds.” It’s by Michelle Crouch for The Charlotte Ledger [and North Carolina Health News]. It’s a story about how some different ambulance patients from North Carolina are finding out that their income gets tapped for debt collection by the state’s EMS agencies, which are government entities, mostly. So the state can take through the EMS up to 10% of your monthly paycheck, or pull from your bank account higher than that, or pull from your tax refunds or lottery winnings. And it’s taking some people a little bit by surprise after they’ve tried to pay off this care and having to face this, but something that the agencies are also saying is necessary to prevent insurers from underpaying them.

Rovner: Oh, sigh.

Raman: Yeah.

Rovner: The endless stream of really good stories on this subject. Alice.

Ollstein: So I chose this piece in Wired by Emily Mullin called “What Tear Gas and Rubber Bullets Do to the Human Body,” thinking a lot about my hometown of Los Angeles, which is under heavy ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] enforcement and National Guard and Marines and who knows who else. So this article is talking about the health impacts of so-called less-lethal police tactics like rubber bullets, like tear gas. And it is about how not only are they sometimes actually lethal — they can kill people and have — but also they have a lot of lingering impacts, especially tear gas. It can exacerbate respiratory problems and even cause brain damage. And so it’s being used very widely and, in some people’s view, indiscriminately right now. And there should be more attention on this, as it can impact completely innocent bystanders and press and who knows who else.

Rovner: Yeah. There’s a long distance between nonlethal and harmless, which I think this story illustrates very well. My extra credit this week is also from The New York Times. It’s called “The Bureaucrat and the Billionaire: Inside DOGE’s Chaotic Takeover of Social Security,” by Alexandra Berzon, Nicholas Nehamas, and Tara Siegel Bernard. It’s about how the White House basically forced Social Security officials to peddle a false narrative that said 40% of calls to the agency’s customer service lines were from scammers — they were not — how DOGE misinterpreted Social Security data and gave a 21-year-old intern access to basically everyone’s personal Social Security information, and how the administration shut down some Social Security offices to punish lawmakers who criticized the president. This is stuff we pretty much knew was happening at the time, and not just in Social Security. But The New York Times now has the receipts. It’s definitely worth reading.

OK. That is this week’s show. Thanks as always to our editor, Emmarie Huetteman, and our producer-engineer, Francis Ying. Also, as always, if you enjoy the podcast, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. We’d appreciate it if you left us a review. That helps other people find us, too. You can email us your comments or questions. We’re at whatthehealth@kff.org. Or you can find me still on X, @jrovner, or on Bluesky, @julierovner. Where are you guys hanging these days? Sandhya.

Raman: @SandhyaWrites on X and the same on Bluesky.

Rovner: Alice.

Ollstein: @alicemiranda on Bluesky and @AliceOllstein on X.

Rovner: Victoria.

Knight: I am @victoriaregisk on X.

Rovner: We will be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

In Axing mRNA Contract, Trump Delivers Another Blow to US Biosecurity, Former Officials Say

The Trump administration’s cancellation of $766 million in contracts to develop mRNA vaccines against potential pandemic flu viruses is the latest blow to national defense, former health security officials said. They warned that the U.S. could be at the mercy of other countries in the […]

PharmaceuticalsThe Trump administration’s cancellation of $766 million in contracts to develop mRNA vaccines against potential pandemic flu viruses is the latest blow to national defense, former health security officials said. They warned that the U.S. could be at the mercy of other countries in the next pandemic.

“The administration’s actions are gutting our deterrence from biological threats,” said Beth Cameron, a senior adviser to the Brown University Pandemic Center and a former director at the White House National Security Council. “Canceling this investment is a signal that we are changing our posture on pandemic preparedness,” she added, “and that is not good for the American people.”

Flu pandemics killed up to 103 million people worldwide last century, researchers estimate.

In anticipation of the next big one, the U.S. government began bolstering the nation’s pandemic flu defenses during the George W. Bush administration. These strategies were designed by the security council and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority at the Department of Health and Human Services, among other agencies. The plans rely on rolling out vaccines rapidly in a pandemic. Moving fast hinges on producing vaccines domestically, ensuring their safety, and getting them into arms across the nation through the public health system.

The Trump administration is undermining each of these steps as it guts health agencies, cuts research and health budgets, and issues perplexing policy changes, health security experts said.

Since President Donald Trump took office, at least half of the security council’s staff have been laid off or left, and the future of BARDA is murky. The nation’s top vaccine adviser, Peter Marks, resigned under pressure in March, citing “the unprecedented assault on scientific truth.”

Most recently, Trump’s clawback of funds for mRNA vaccine development put Americans on shakier ground in the next pandemic. “When the need hits and we aren’t ready, no other country will come to our rescue and we will suffer greatly,” said Rick Bright, an immunologist and a former BARDA director.

Countries that produced their own vaccines in the covid-19 pandemic had first dibs on the shots. While the United States, home to Moderna and Pfizer, rolled out second doses of mRNA vaccines in 2021, hundreds of thousands of people in countries that didn’t manufacture vaccines died waiting for them.

The most pertinent pandemic threat today is the bird flu virus H5N1. Researchers around the world were alarmed when it began spreading among cattle in the U.S. last year. Cows are closer to humans biologically than birds, indicating that the virus had evolved to thrive in cells like our own.

As hundreds of herds and dozens of people were infected in the U.S., the Biden administration funded Moderna to develop bird flu vaccines using mRNA technology. As part of the agreement, the U.S. government stipulated it could purchase doses in advance of a pandemic. That no longer stands.

Researchers can make bird flu vaccines in other ways, but mRNA vaccines are developed much more quickly because they don’t rely on finicky biological processes, such as growing elements of vaccines in chicken eggs or cells kept alive in laboratory tanks.

Time matters because flu viruses mutate constantly, and vaccines work better when they match whatever variant is circulating.

Developing vaccines within eggs or cells can take 10 months after the genetic sequence of a variant is known, Bright said. And relying on eggs presents an additional risk when it comes to bird flu because a pandemic could wipe out billions of chickens, crashing egg supplies.

Decades-old methods that rely on inactivated flu viruses are riskier for researchers and time-consuming. Still the Trump administration invested $500 million into this approach, which was largely abandoned by the 1980s after it caused seizures in children.

“This politicized regression is baffling,” Bright said.

A bird flu pandemic may begin quietly in the U.S. if the virus evolves to spread between people but no one is tested at first. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s dashboard suggests that only 10 farmworkers have been tested for the bird flu since March. Because of their close contact with cattle and poultry, farmworkers are at highest risk of infection.

As with many diseases, only a fraction of people with the bird flu become severely sick. So the first sign that the virus is widespread might be a surge in hospital cases.

“We’d need to immediately make vaccines,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

The U.S. government could scale up production of existing bird flu vaccines developed in eggs or cells. However, these vaccines target an older strain of H5N1 and their efficacy against the virus circulating now is unknown.

In addition to the months it takes to develop an updated version within eggs or cells, Rasmussen questioned the ability of the government to rapidly test and license updated shots, with a quarter of HHS staff gone. If the Senate approves Trump’s proposed budget, the agency faces about $32 billion in cuts.

Further, the Trump administration’s cuts to biomedical research and its push to slash grant money for overhead costs could undermine academic hospitals, rendering them unable to conduct large clinical trials. And its cuts to the CDC and to public health funds to states mean that fewer health officials will be available in an emergency.

“You can’t just turn this all back on,” Rasmussen said. “The longer it takes to respond, the more people die.”

Researchers suggest other countries would produce bird flu vaccines first. “The U.S. may be on the receiving end like India was, where everyone — rich people, too — got vaccines late,” said Achal Prabhala, a public health researcher in India at medicines access group AccessIBSA.

He sits on the board of a World Health Organization initiative to improve access to mRNA vaccines in the next pandemic. A member of the initiative, the company Sinergium Biotech in Argentina, is testing an mRNA vaccine against the bird flu. If it works, Sinergium will share the intellectual property behind the vaccine with about a dozen other groups in the program from middle-income countries so they can produce it.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, an international partnership headquartered in Norway, is providing funds to research groups developing rapid-response vaccine technology, including mRNA, in South Korea, Singapore, and France. And CEPI committed up to $20 million to efforts to prepare for a bird flu pandemic. This year, the Indian government issued a call for grant applications to develop mRNA vaccines for the bird flu, warning it “poses a grave public health risk.”

Pharmaceutical companies are investing in mRNA vaccines for the bird flu as well. However, Prabhala says private capital isn’t sufficient to bring early-stage vaccines through clinical trials and large-scale manufacturing. That’s because there’s no market for bird flu vaccines until a pandemic hits.

Limited supplies means the United States would have to wait in line for mRNA vaccines made abroad. States and cities may compete against one another for deals with outside governments and companies, like they did for medical equipment at the peak of the covid pandemic.

“I fear we will once again see the kind of hunger games we saw in 2020,” Cameron said.

In an email response to queries, HHS communications director Andrew Nixon said, “We concluded that continued investment in Moderna’s H5N1 mRNA vaccine was not scientifically or ethically justifiable.” He added, “The decision reflects broader concerns about the use of mRNA platforms—particularly in light of mounting evidence of adverse events associated with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines.”

Nixon did not back up the claim by citing analyses published in scientific journals.

In dozens of published studies, researchers have found that mRNA vaccines against covid are safe. For example, a placebo-controlled trial of more than 30,000 people in the U.S. found that adverse effects of Moderna’s vaccine were rare and transient, whereas 30 participants in the placebo group suffered severe cases of covid and one died.

More recently, a study revealed that three of nearly 20,000 people who got Moderna’s vaccines and booster had significant adverse effects related to the vaccine, which resolved within a few months. Covid, on the other hand, killed four people during the course of the study.

As for concerns about the heart issue, myocarditis, a study of 2.5 million people who got at least one dose of Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine revealed about 2 cases per 100,000 people. Covid causes 10 to 105 myocarditis cases per 100,000.

Nonetheless, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who founded an anti-vaccine organization, has falsely called covid shots “the deadliest vaccine ever made.” And without providing evidence, he said the 1918 flu pandemic “came from vaccine research.”

Politicized mistrust in vaccines has grown. Far more Republicans said they trust Kennedy to provide reliable information on vaccines than their local health department or the CDC in a recent KFF poll: 73% versus about half.

Should the bird flu become a pandemic in the next few years, Rasmussen said, “we will be screwed on multiple levels.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

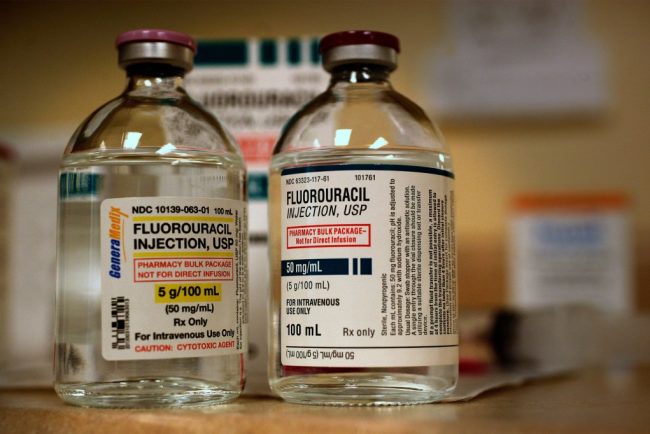

Two Patients Faced Chemo. The One Who Survived Demanded a Test To See if It Was Safe.

JoEllen Zembruski-Ruple, while in the care of New York City’s renowned Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, swallowed the first three chemotherapy pills to treat her squamous cell carcinoma on Jan. 29, her family members said. They didn’t realize the drug could kill her. Six days […]

PharmaceuticalsJoEllen Zembruski-Ruple, while in the care of New York City’s renowned Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, swallowed the first three chemotherapy pills to treat her squamous cell carcinoma on Jan. 29, her family members said. They didn’t realize the drug could kill her.

Six days later, Zembruski-Ruple went to Sloan Kettering’s urgent care department to treat sores in her mouth and swelling around her eyes. The hospital diagnosed oral yeast infection and sent her home, her sister and partner said. Two days later, they said, she returned in agony — with severe diarrhea and vomiting — and was admitted. “Enzyme deficiency,” Zembruski-Ruple texted a friend.

The 65-year-old, a patient advocate who had worked for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and other groups, would never go home.

Covered in bruises and unable to swallow or talk, she eventually entered hospice care and died March 25 from the very drug that was supposed to extend her life, said her longtime partner, Richard Khavkine. Zembruski-Ruple was deficient in the enzyme that metabolizes capecitabine, the chemotherapy drug she took, said Khavkine and Susan Zembruski, one of her sisters. Zembruski-Ruple was among about 1,300 Americans each year who die from the toxic effects of that pill or its cousin, the IV drug fluorouracil known as 5-FU.

Doctors can test for the deficiency — and then either switch drugs or lower the dosage if patients have a genetic variant that carries risk. The FDA approved an antidote in 2015, but it’s expensive and must be administered within four days of the first chemotherapy treatment.

Newer cancer drugs sometimes include a companion diagnostic to determine whether a drug works with an individual patient’s genetics. But 5-FU went on the market in 1962 and sells for about $17 a dose; producers of its generic aren’t seeking approval for toxicity tests, which typically cost hundreds of dollars. Doctors have only gradually understood which gene variants are dangerous in which patients, and how to deal with them, said Alan Venook, a colorectal and liver cancer specialist at the University of California-San Francisco.

By the time Zembruski-Ruple’s doctors told her she had the deficiency, she had been on the drug for eight days, said Khavkine, who watched over his partner with her sister throughout the seven-week ordeal.

Khavkine said he “would have asked for the test” if he had known about it, but added “nobody told us about the possibility of this deficiency.” Zembruski-Ruple’s sister also said she wasn’t warned about the fatal risks of the chemo, or told about the test.

“They never said why they didn’t test her,” Zembruski said. “If the test existed, they should have said there is a test. If they said, ‘Insurance won’t cover it,’ I would have said, ‘Here’s my credit card.’ We should have known about it.”

Guidance Moves at a Glacial Pace

Despite growing awareness of the deficiency, and an advocacy group made up of grieving friends and relatives who push for routine testing of all patients before they take the drug, the medical establishment has moved slowly.

A panel of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, or NCCN — specialists from Sloan Kettering and other top research centers — until recently did not recommend testing, and the FDA does not require it.

In response to a query from KFF Health News about its policy, Sloan Kettering spokesperson Courtney Nowak said the hospital treats patients “in accordance with NCCN guidelines.” She said the hospital would not discuss a patient’s care.

On Jan. 24, the FDA issued a warning about the enzyme deficiency in which it urged health care providers to “inform patients prior to treatment” about the risks of taking 5-FU and capecitabine.

On March 31 — six days after Zembruski-Ruple’s death — the network’s expert panel for most gastrointestinal cancers took a first step toward recommending testing for the deficiency.

Worried that President Donald Trump’s FDA might do nothing, Venook said, the panel — whose guidance shapes the practices of oncologists and health insurers — recommended that doctors consider testing before dosing patients with 5-FU or capecitabine.

However, its guidance stated that “no specific test is recommended at this time,” citing a lack of data to “inform dose adjustments.”

Sloan Kettering “will consider this guidance in developing personalized treatment plans for each patient,” Nowak told KFF Health News.

The new NCCN guidance was “not the blanket recommendation we were working toward, but it is a major step toward our ultimate goal,” said Kerin Milesky, a public health official in Brewster, Massachusetts, who’s part of an advocacy group for testing. Her husband, Larry, died two years ago at age 73 after a single treatment of capecitabine.

European drug regulators began urging oncologists to test patients for deficiency in May 2020. Patients with potentially risky genetics are started on a half-dose of the cancer drug. If they suffer no major toxicity, the dose is increased.

A Lifesaving Ultimatum?

Emily Alimonti, a 42-year-old biotech salesperson in upstate New York, chose that path before starting capecitabine treatment in December. She said her doctors — including an oncologist at Sloan Kettering — told her they didn’t do deficiency testing, but Alimonti insisted. “Nope,” she said. “I’m not starting it until I get the test back.”

The test showed that Alimonti had a copy of a risky gene variant, so doctors gave her a lower dose of the drug. Even that has been hard to tolerate; she’s had to skip doses because of low white blood cell counts, Alimonti said. She still doesn’t know whether her insurer will cover the test.

Around 300,000 people are treated with 5-FU or capecitabine in the United States each year, but its toxicity could well have prevented FDA approval were it up for approval today. Short of withdrawing a drug, however, U.S. regulators have little power to manage its use. And 5-FU and capecitabine are still powerful tools against many cancers.

At a January workshop that included FDA officials and cancer specialists, Venook, the NCCN panel’s co-chair, asked whether it was reasonable to recommend that doctors obtain a genetic test “without saying what to do with the result.”

But Richard Pazdur, the FDA’s top cancer expert, said it was time to end the debate and commence testing, even if the results could be ambiguous. “If you don’t have the information, how do you have counseling?” he asked.

Two months later, Venook’s panel changed course. The price of tests has fallen below $300 and results can be returned as soon as three days, Venook said. Doubts about the FDA’s ability to further confront the issue spurred the panel’s change of heart, he said.

“I don’t know if FDA is going to exist tomorrow,” Venook told KFF Health News. “They’re taking a wrecking ball to common sense, and that’s one of the reasons we felt we had to go forward.”

On May 20, the FDA posted a Federal Register notice seeking public input on the issue, a move that suggested it was considering further action.

Venook said he often tests his own patients, but the results can be fuzzy. If the test finds two copies of certain dangerous gene variants in a patient, he avoids using the drug. But such cases are rare — and Zembruski-Ruple was one of them, according to her sister and Khavkine.

Many more patients have a single copy of a suspect gene, an ambiguous result that requires clinical judgment to assess, Venook said.

A full-gene scan would provide more information but adds expense and time, and even then the answer may be murky, Venook said. He worries that starting patients on lower doses could mean fewer cures, especially for newly diagnosed colon cancer patients.

Power Should Rest With Patients

Scott Kapoor, a Toronto-area emergency room physician whose brother Anil, a much-loved urologist and surgeon, died of 5-FU toxicity at age 58 in 2023, views Venook’s arguments as medical paternalism. Patients should decide whether to test and what to do with the results, he said.

“What’s better — don’t tell the patient about the test, don’t test them, potentially kill them in 20 days?” he said. “Or tell them about the testing while warning that potentially the cancer will kill them in a year?”

“People say oncologists don’t know what to do with the information,” said Karen Merritt, whose mother died after an infusion of 5-FU in 2014. “Well, I’m not a doctor, but I can understand the Mayo Clinic report on it.”

The Mayo Clinic recommends starting patients on half a dose if they have one suspect gene variant. And “the vast majority of patients will be able to start treatment without delays,” Daniel Hertz, a clinical pharmacologist from the University of Michigan, said at the January meeting.

Some hospitals began testing after patients died because of the deficiency, said Lindsay Murray, of Andover, Massachusetts, who has advocated for widespread testing since her mother was treated with capecitabine and died in 2021.

In some cases, Venook said, relatives of dead patients have sued hospitals, leading to settlements.

Kapoor said his brother — like many patients of non-European origin — had a gene variant that hasn’t been widely studied and isn’t included in most tests. But a full-gene scan would have detected it, Kapoor said, and such scans can also be done for a few hundred dollars.

The cancer network panel’s changed language is disappointing, he said, though “better than nothing.”

In video tributes to Zembruski-Ruple, her friends, colleagues, and clients remembered her as kind, helpful, and engaging. “JoEllen was beautiful both inside and out,” said Barbara McKeon, a former colleague at the MS Society. “She was funny, creative, had a great sense of style.”

“JoEllen had this balance of classy and playful misbehavior,” psychotherapist Anastatia Fabris said. “My beautiful, vibrant, funny, and loving friend JoEllen.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

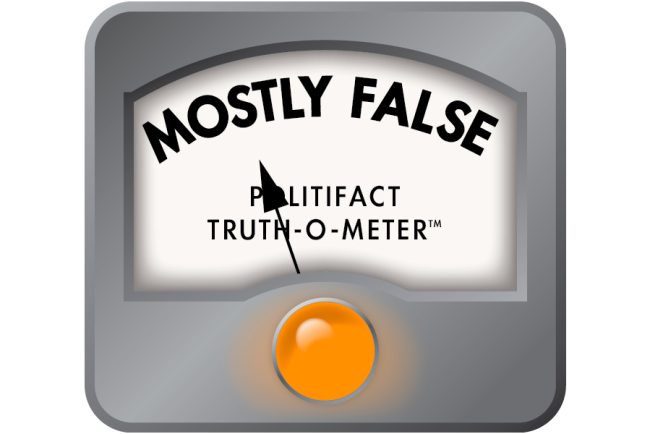

Trump Exaggerates Speed and Certainty of Prescription Drug Price Reductions

Under a new executive order, prescription drug prices will be reduced “almost immediately.” President Donald Trump, in a May 11 post on Truth Social President Donald Trump expressed high hopes for an executive order to reduce drug prices. On May 11, the day before he […]

PharmaceuticalsUnder a new executive order, prescription drug prices will be reduced “almost immediately.”

President Donald Trump, in a May 11 post on Truth Social

President Donald Trump expressed high hopes for an executive order to reduce drug prices.

On May 11, the day before he held a White House event to sign the executive order, Trump posted on Truth Social, “Prescription Drug and Pharmaceutical prices will be REDUCED, almost immediately, by 30% to 80%.”

However, the executive order’s text, unveiled May 12, undercut the president’s description of how soon consumers could experience this potential boon.

The idea of the executive order, he said, was to lower high prescription drug costs in the U.S. to levels more typical in other countries.

“We’re going to equalize,” Trump said at the order signing. “We’re all going to pay the same. We’re going to pay what Europe’s going to pay.”

Experts said Trump’s action could lower the cost of prescription drugs, perhaps by the 30% to 80% Trump said, but they cautioned that the order’s required procedural steps would make it far from an immediate fix.

The executive order says that within 30 days, administration officials must determine and communicate to drugmakers “most-favored-nation price targets,” to push the companies to “bring prices for American patients in line with comparably developed nations.”

After an unspecified period of time, the administration will gauge whether “significant progress” toward lower pricing has been achieved. If not, the order requires the secretary of Health and Human Services to “propose a rulemaking plan to impose most-favored-nation pricing,” which could take months or years to take effect.

“Executive orders are wish lists,” said Joseph Antos, a senior fellow emeritus in health care policy at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. The order “hopes that manufacturers will unilaterally lower U.S. prices. The legal authority to intervene in the market is unclear if this implausible scenario doesn’t happen.”

When contacted for comment, the White House did not provide evidence that the executive order would provide immediate results.

Why Do Americans Pay More for Prescriptions?

There is wide agreement that drug prices are unusually high in the U.S. The prices Americans pay for pharmaceuticals are nearly three times the average among a group of other industrialized countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

A study by the Rand Corp., a nonpartisan research organization, found that, across all drugs, U.S. prices were 2.78 times as high as the average prices across 33 OECD countries. The gap was even wider for brand-name drugs, with U.S. prices averaging 4.22 times as much.

The U.S. has lower prices than comparable nations for unbranded, generic drugs, which account for about 90% of filled prescriptions in the U.S. But generics account for only a fifth of U.S. prescription drug spending.

Experts cite several reasons for this pricing discrepancy.

One is that the U.S. has more limited price negotiation with drug manufacturers than other countries do. Often, if another country fails to find the extra cost of a new drug is justified by improved results, it’ll reject the drug application. Some countries also set price controls.

Another factor is patent exclusivity. Over the years, U.S. pharmaceutical companies have used strong legal protections to amass patents that can keep generic competitors from the marketplace.Drug companies have also argued that high prices help pay for research and development of new and improved pharmaceuticals. When Trump released the executive order, Stephen J. Ubl, president and CEO of the drug industry group Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, said in a statement, “It would mean less treatments and cures and would jeopardize the hundreds of billions our member companies are planning to invest in America.” (In Trump’s May 13 interview with Fox News’ Sean Hannity, Trump offered a different picture of what drug company officials have told him; he said they agreed “it’s time” to lower U.S. prices.)

Recent studies have cast doubt on the idea that high prices pay for research and development. A 2023 study found that from 1999 to 2018, the world’s 15 largest biopharmaceutical companies spent more on selling and general administrative activities, which include marketing, than on research and development. The study also said most new medicines developed during this period offered little to no clinical benefit over existing treatments.

The long-standing reality of high U.S. drug prices has driven Democratic and Republican efforts to bring them down. Then-President Joe Biden signed legislation to require Medicare, the federal health care program that covers Americans over 65, to negotiate prices with the makers of some popular, high-cost medicines. And Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) has made lowering drug prices a cornerstone issue during his political career.

During his first term, Trump sought to lower prices for certain drugs under Medicare, but the courts blocked the move on procedural grounds.

Trump’s drug-price push could attract bipartisan support, experts said.

Jonathan Cohn, who has worked for several left-of-center media outlets and wrote two books on health care policy, offered measured praise for Trump’s executive order in The Bulwark, a publication generally critical of Trump, calling it “a serious policy initiative, one that credible people think could bring some relief on drug prices.”

Andrew Mulcahy, a Rand Corp. senior health economist, said one part of Trump’s statement — the possibility of a 30% to 80% price reduction — is plausible.

“Of course, the devil’s in the policy design and implementation details,” Mulcahy said. “But at first blush, a savings of roughly two-thirds on what we spend now for drugs seems in line” with what Rand’s research has shown.

What Would Trump’s Executive Order Do?

Referring to high U.S. drug prices, Trump told Hannity that “I ended it” by issuing the executive order. But that’s not how the order is structured.

The executive order makes plain that any actions will not happen quickly.

“That ‘almost’ in ‘almost immediately’ is doing a lot of work,” Mulcahy said, referring to Trump’s statement.

The executive order also could face court challenges, just as Trump’s first-term executive order did.

“It seems unlikely that the federal government can set prices for drugs outside of the Medicare program,” Antos said. If Trump wants reduced prices to benefit all U.S. consumers, experts said, Congress will likely have to pass new legislation. While executive orders direct federal agencies what to do, requiring action from privately owned companies likely would require legislation passed by Congress, experts said.

If Congress gets involved, that will not only tack on extra time, but it also could draw opposition from the Republican majority in one or both chambers. Historically, Antos said, “federal price controls are anathema for many Republicans in Congress.”

Our Ruling

Trump said that, because of his new executive order, prescription drug prices would be reduced “almost immediately.”

Experts said that if the goals of the executive order are achieved, price reductions would not happen “almost immediately.”

The order sets out a 30-day period to develop pricing targets for drugmakers, followed by an unspecified amount of time to see if companies achieve the targets. If they don’t, a formal rulemaking process would begin, requiring months or even years. And if Trump intends to lower prices for all consumers, not only those who have federal coverage such as Medicare, Congress will likely have to pass a law to do it.

Trump gives the impression that Americans will shortly see steep decreases in what they pay for prescription drugs. But even if the executive order acts as intended — which would require a lot to go right — it could take months or years.

The statement contains an element of truth but ignores evidence that would give a different impression. We rate it Mostly False.

Sources

Donald Trump, Truth Social post, May 11, 2025

White House, “Delivering Most-Favored-Nation Prescription Drug Pricing to American Patients,” May 12, 2025

Rand Corp., “International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Estimates Using 2022 Data,” February 2024

Government Accountability Office, “U.S. Prices for Selected Brand Drugs Were Higher on Average Than Prices in Australia, Canada, and France,” March 2021

The BMJ, “High Drug Prices Are Not Justified by Industry’s Spending on Research and Development,” Feb. 15, 2023

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, “PhRMA Statement on Most Favored Nation Executive Order,” May 12, 2025

USA Today, “RFK Jr. Spars With Bernie Sanders Over Who Did Most To Curb Prescription Drug Prices,” May 12, 2025

The Associated Press, “Trump Plan To Curb Drug Costs Dealt Setback in Court,” Dec. 23, 2020

The Associated Press, “White House Says Prescription Drug Deals Will Produce Billions in Savings for Taxpayers, Seniors,” Aug. 15, 2024

PolitiFact, “For the Most Part, the US Pays Double for Prescriptions Compared With Other Countries, as Biden Says,” March 4, 2024

Email interview with Joseph Antos, senior fellow emeritus in health care policy at the American Enterprise Institute, May 12, 2025

Email interview with Andrew Mulcahy, senior health economist with Rand Corp., May 12, 2025