by Admin

In Axing mRNA Contract, Trump Delivers Another Blow to US Biosecurity, Former Officials Say

The Trump administration’s cancellation of $766 million in contracts to develop mRNA vaccines against potential pandemic flu viruses is the latest blow to national defense, former health security officials said. They warned that the U.S. could be at the mercy of other countries in the […]

Pharmaceuticals

by Admin

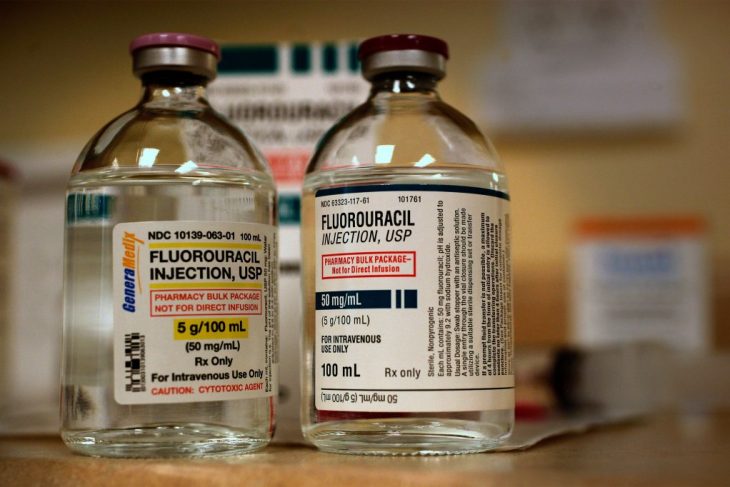

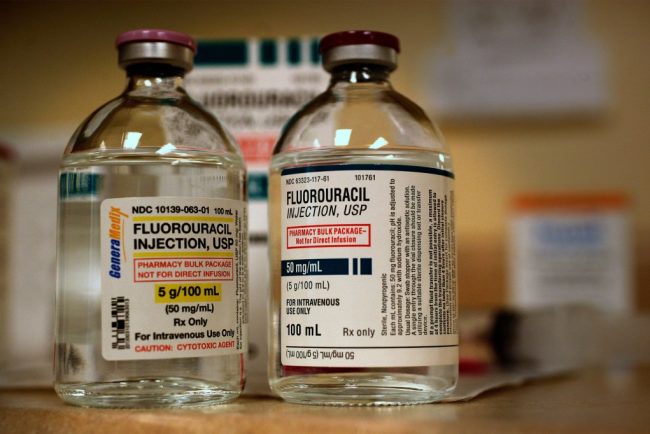

Two Patients Faced Chemo. The One Who Survived Demanded a Test To See if It Was Safe.

JoEllen Zembruski-Ruple, while in the care of New York City’s renowned Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, swallowed the first three chemotherapy pills to treat her squamous cell carcinoma on Jan. 29, her family members said. They didn’t realize the drug could kill her. Six days […]

Pharmaceuticals

by Admin

Trump Exaggerates Speed and Certainty of Prescription Drug Price Reductions

Under a new executive order, prescription drug prices will be reduced “almost immediately.” President Donald Trump, in a May 11 post on Truth Social President Donald Trump expressed high hopes for an executive order to reduce drug prices. On May 11, the day before he […]

Pharmaceuticals

Honey, Sweetie, Dearie: The Perils of Elderspeak

by Admin

A prime example of elderspeak: Cindy Smith was visiting her father in his assisted living apartment in Roseville, California. An aide who was trying to induce him to do something — Smith no longer remembers exactly what — said, “Let me help you, sweetheart.” “He […]

PharmaceuticalsA prime example of elderspeak: Cindy Smith was visiting her father in his assisted living apartment in Roseville, California. An aide who was trying to induce him to do something — Smith no longer remembers exactly what — said, “Let me help you, sweetheart.”

“He just gave her The Look — under his bushy eyebrows — and said, ‘What, are we getting married?’” recalled Smith, who had a good laugh, she said. Her father was then 92, a retired county planner and a World War II veteran; macular degeneration had reduced the quality of his vision, and he used a walker to get around, but he remained cognitively sharp.

“He wouldn’t normally get too frosty with people,” Smith said. “But he did have the sense that he was a grown-up and he wasn’t always treated like one.”

People understand almost intuitively what “elderspeak” means. “It’s communication to older adults that sounds like baby talk,” said Clarissa Shaw, a dementia care researcher at the University of Iowa College of Nursing and a co-author of a recent article that helps researchers document its use.

“It arises from an ageist assumption of frailty, incompetence, and dependence.”

Its elements include inappropriate endearments. “Elderspeak can be controlling, kind of bossy, so to soften that message there’s ‘honey,’ ‘dearie,’ ‘sweetie,’” said Kristine Williams, a nurse gerontologist at the University of Kansas School of Nursing and another co-author of the article.

“We have negative stereotypes of older adults, so we change the way we talk.”

Or caregivers may resort to plural pronouns: Are we ready to take our bath? There, the implication “is that the person’s not able to act as an individual,” Williams said. “Hopefully, I’m not taking the bath with you.”

Sometimes, elderspeakers employ a louder volume, shorter sentences, or simple words intoned slowly. Or they may adopt an exaggerated, singsong vocal quality more suited to preschoolers, along with words like “potty” or “jammies.”

With what are known as tag questions — It’s time for you to eat lunch now, right? — “You’re asking them a question but you’re not letting them respond,” Williams explained. “You’re telling them how to respond.”

Studies in nursing homes show how commonplace such speech is. When Williams, Shaw, and their team analyzed video recordings of 80 interactions between staff and residents with dementia, they found that 84% involved some form of elderspeak.

“Most of elderspeak is well intended. People are trying to show they care,” Williams said. “They don’t realize the negative messages that come through.”

For example, among nursing home residents with dementia, studies have found a relationship between exposure to elderspeak and behaviors collectively known as resistance to care.

“People can turn away or cry or say no,” Williams explained. “They may clench their mouths shut when you’re trying to feed them.” Sometimes, they push caregivers away or strike them.

She and her team developed a training program called CHAT, for Changing Talk: three hourlong sessions that include videos of communication between staff members and patients, intended to reduce elderspeak.

It worked. Before the training, in 13 nursing homes in Kansas and Missouri, almost 35% of the time spent in interactions consisted of elderspeak; that share dropped to about 20% afterward.

Furthermore, resistant behaviors accounted for almost 36% of the time spent in encounters; after training, that proportion fell to about 20%.

A study conducted in a Midwestern hospital, again among patients with dementia, found the same sort of decline in resistance behavior.

What’s more, CHAT training in nursing homes was associated with lower use of antipsychotic drugs. Though the results did not reach statistical significance, due in part to the small sample size, the research team deemed them “clinically significant.”

“Many of these medications have a black box warning from the FDA,” Williams said of the drugs. “It’s risky to use them in frail, older adults” because of their side effects.

Now, Williams, Shaw, and their colleagues have streamlined the CHAT training and adapted it for online use. They are examining its effects in about 200 nursing homes nationwide.

Even without formal training programs, individuals and institutions can combat elderspeak. Kathleen Carmody, owner of Senior Matters Home Health Care and Consulting in Columbus, Ohio, cautions her aides to address clients as Mr. or Mrs. or Ms., “unless or until they say, ‘Please call me Betty.’”

In long-term care, however, families and residents may worry that correcting the way staff members speak could create antagonism.

A few years ago, Carol Fahy was fuming about the way aides at an assisted living facility in suburban Cleveland treated her mother, who was blind and had become increasingly dependent in her 80s.

Calling her “sweetie” and “honey babe,” the staff “would hover and coo, and they put her hair up in two pigtails on top of her head, like you would with a toddler,” said Fahy, a psychologist in Kaneohe, Hawaii.

Although she recognized the aides’ agreeable intentions, “there’s a falseness about it,” she said. “It doesn’t make someone feel good. It’s actually alienating.”

Fahy considered discussing her objections with the aides, but “I didn’t want them to retaliate.” Eventually, for several reasons, she moved her mother to another facility.

Yet objecting to elderspeak need not become adversarial, Shaw said. Residents and patients — and people who encounter elderspeak elsewhere, because it’s hardly limited to health care settings — can politely explain how they prefer to be spoken to and what they want to be called.

Cultural differences also come into play. Felipe Agudelo, who teaches health communications at Boston University, pointed out that in certain contexts a diminutive or term of endearment “doesn’t come from underestimating your intellectual ability. It’s a term of affection.”

He emigrated from Colombia, where his 80-year-old mother takes no offense when a doctor or health care worker asks her to “tómese la pastillita” (take this little pill) or “mueva la manito” (move the little hand).

That’s customary, and “she feels she’s talking to someone who cares,” Agudelo said.

“Come to a place of negotiation,” he advised. “It doesn’t have to be challenging. The patient has the right to say, ‘I don’t like your talking to me that way.’”

In return, the worker “should acknowledge that the recipient may not come from the same cultural background,” he said. That person can respond, “This is the way I usually talk, but I can change it.”

Lisa Greim, 65, a retired writer in Arvada, Colorado, pushed back against elderspeak recently when she enrolled in Medicare drug coverage.

Suddenly, she recounted in an email, a mail-order pharmacy began calling almost daily because she hadn’t filled a prescription as expected.

These “gently condescending” callers, apparently reading from a script, all said, “It’s hard to remember to take our meds, isn’t it?” — as if they were swallowing pills together with Greim.

Annoyed by their presumption, and their follow-up question about how frequently she forgot her medications, Greim informed them that having stocked up earlier, she had a sufficient supply, thanks. She would reorder when she needed more.

Then, “I asked them to stop calling,” she said. “And they did.”

The New Old Age is produced through a partnership with The New York Times.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP

The Host Julie Rovner KFF Health News @jrovner @julierovner.bsky.social Read Julie’s stories. Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the […]

PharmaceuticalsThe Host

Julie Rovner

KFF Health News

Julie Rovner is chief Washington correspondent and host of KFF Health News’ weekly health policy news podcast, “What the Health?” A noted expert on health policy issues, Julie is the author of the critically praised reference book “Health Care Politics and Policy A to Z,” now in its third edition.

After narrowly passing a budget resolution this spring foreshadowing major Medicaid cuts, Republicans in Congress are having trouble agreeing on specific ways to save billions of dollars from a pool of funding that pays for the program without cutting benefits on which millions of Americans rely. Moderates resist changes they say would harm their constituents, while fiscal conservatives say they won’t vote for smaller cuts than those called for in the budget resolution. The fate of President Donald Trump’s “one big, beautiful bill” containing renewed tax cuts and boosted immigration enforcement could hang on a Medicaid deal.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration surprised those on both sides of the abortion debate by agreeing with the Biden administration that a Texas case challenging the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone should be dropped. It’s clear the administration’s request is purely technical, though, and has no bearing on whether officials plan to protect the abortion pill’s availability.

This week’s panelists are Julie Rovner of KFF Health News, Anna Edney of Bloomberg News, Maya Goldman of Axios, and Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Panelists

Anna Edney

Bloomberg News

Maya Goldman

Axios

Sandhya Raman

CQ Roll Call

Among the takeaways from this week’s episode:

- Congressional Republicans are making halting progress on negotiations over government spending cuts. As hard-line House conservatives push for deeper cuts to the Medicaid program, their GOP colleagues representing districts that heavily depend on Medicaid coverage are pushing back. House Republican leaders are eying a Memorial Day deadline, and key committees are scheduled to review the legislation next week — but first, Republicans need to agree on what that legislation says.

- Trump withdrew his nomination of Janette Nesheiwat for U.S. surgeon general amid accusations she misrepresented her academic credentials and criticism from the far right. In her place, he nominated Casey Means, a physician who is an ally of HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s and a prominent advocate of the “Make America Healthy Again” movement.

- The pharmaceutical industry is on alert as Trump prepares to sign an executive order directing agencies to look into “most-favored-nation” pricing, a policy that would set U.S. drug prices to the lowest level paid by similar countries. The president explored that policy during his first administration, and the drug industry sued to stop it. Drugmakers are already on edge over Trump’s plan to impose tariffs on drugs and their ingredients.

- And Kennedy is scheduled to appear before the Senate’s Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee next week. The hearing would be the first time the secretary of Health and Human Services has appeared before the HELP Committee since his confirmation hearings — and all eyes are on the committee’s GOP chairman, Sen. Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, a physician who expressed deep concerns at the time, including about Kennedy’s stances on vaccines.

Also this week, Rovner interviews KFF Health News’ Lauren Sausser, who co-reported and co-wrote the latest KFF Health News’ “Bill of the Month” installment, about an unexpected bill for what seemed like preventive care. If you have an outrageous, baffling, or infuriating medical bill you’d like to share with us, you can do that here.

Plus, for “extra credit” the panelists suggest health policy stories they read this week that they think you should read, too:

Julie Rovner: NPR’s “Fired, Rehired, and Fired Again: Some Federal Workers Find They’re Suddenly Uninsured,” by Andrea Hsu.

Maya Goldman: Stat’s “Europe Unveils $565 Million Package To Retain Scientists, and Attract New Ones,” by Andrew Joseph.

Anna Edney: Bloomberg News’ “A Former TV Writer Found a Health-Care Loophole That Threatens To Blow Up Obamacare,” by Zachary R. Mider and Zeke Faux.

Sandhya Raman: The Louisiana Illuminator’s “In the Deep South, Health Care Fights Echo Civil Rights Battles,” by Anna Claire Vollers.

Also mentioned in this week’s podcast:

- ProPublica’s series “Life of the Mother: How Abortion Bans Lead to Preventable Deaths,” by Kavitha Surana, Lizzie Presser, Cassandra Jaramillo, and Stacy Kranitz, and the winner of the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for public service journalism.

- The New York Times’ “G.O.P. Targets a Medicaid Loophole Used by 49 States To Grab Federal Money,” by Margot Sanger-Katz and Sarah Kliff.

- KFF Health News’ “Seeking Spending Cuts, GOP Lawmakers Target a Tax Hospitals Love to Pay,” by Phil Galewitz.

- Axios’ “Out-of-Pocket Drug Spending Hit $98B in 2024: Report,” by Maya Goldman.

click to open the transcript

Transcript: Cutting Medicaid Is Hard — Even for the GOP

[Editor’s note: This transcript was generated using both transcription software and a human’s light touch. It has been edited for style and clarity.]

Julie Rovner: Hello and welcome back to “What the Health?” I’m Julie Rovner, chief Washington correspondent for KFF Health News, and I’m joined by some of the best and smartest health reporters in Washington. We’re taping this week on Thursday, May 8, at 10 a.m. As always, news happens fast and things might have changed by the time you hear this. So, here we go.

Today we are joined via a videoconference by Anna Edney of Bloomberg News.

Anna Edney: Hi, everybody.

Rovner: Maya Goldman of Axios News.

Maya Goldman: Great to be here.

Rovner: And Sandhya Raman of CQ Roll Call.

Sandhya Raman: Good morning, everyone.

Rovner: Later in this episode we’ll have my “Bill of the Month” interview with my KFF Health News colleague Lauren Sausser. This month’s patient got preventive care they assumed would be covered by their Affordable Care Act health plan, except it wasn’t. But first, this week’s news.

We’re going to start on Capitol Hill, where Sandhya is coming directly from, where regular listeners to this podcast will be not one bit surprised that Republicans working on President [Donald] Trump’s one “big, beautiful” budget reconciliation bill are at an impasse over how and how deeply to cut the Medicaid program. Originally, the House Energy and Commerce Committee was supposed to mark up its portion of the bill this week, but that turned out to be too optimistic. Now they’re shooting for next week, apparently Tuesday or so, they’re saying, and apparently that Memorial Day goal to finish the bill is shifting to maybe the Fourth of July? But given what’s leaking out of the closed Republican meetings on this, even that might be too soon. Where are we with these Medicaid negotiations?

Raman: I would say a lot has been happening, but also a lot has not been happening. I think that anytime we’ve gotten any little progress on knowing what exactly is at the top of the list, it gets walked back. So earlier this week we had a meeting with a lot of the moderates in Speaker [Mike] Johnson’s office and trying to get them on board with some of the things that they were hesitant about, and following the meeting, Speaker Johnson had said that two of the things that have been a little bit more contentious — changing the federal match for the expansion population and instituting per capita caps for states — were off the table. But the way that he phrased it is kind of interesting in that he said stay tuned and that it possibly could change.

And so then yesterday when we were hearing from the Energy and Commerce Committee, it seemed like these things are still on the table. And then Speaker Johnson has kind of gone back on that and said, I said it was likely. So every time we kind of have any sort of change, it’s really unclear if these things are in the mix, outside the mix. When we pulled them off the table, we had a lot of the hard-line conservatives get really upset about this because it’s not enough savings. So I think any way that you push it with such narrow margins, it’s been difficult to make any progress, even though they’ve been having a lot of meetings this week.

Rovner: One of the things that surprised me was apparently the Senate Republicans are weighing in. The Senate Republicans who aren’t even set to make Medicaid cuts under their version of the budget resolution are saying that the House needs to go further. Where did that come from?

Raman: It’s just been a difficult process to get anything across. I mean, in the House side, a lot of it has been, I think, election-driven. You see the people that are not willing to make as many concessions are in competitive districts. The people that want to go a little bit more extreme on what they’re thinking are in much more safe districts. And then in the Senate, I think there’s a lot more at play just because they have longer terms, they have more to work with. So some of the pushback has been from people that it would directly affect their states or if the governors have weighed in. But I think that there are so many things that they do want to get done, since there is much stronger agreement on some of the immigration stuff and the taxes that they want to find the savings somewhere. If they don’t find it, then the whole thing is moot.

Rovner: So meanwhile, the Congressional Budget Office at the request of Democrats is out with estimates of what some of these Medicaid options would mean for coverage, and it gives lie to some of these Republican claims that they can cut nearly a trillion dollars from Medicaid without touching benefits, right? I mean all of these — and Maya, your nodding.

Goldman: Yeah.

Rovner: All of these things would come with coverage losses.

Goldman: Yeah, I think it’s important to think about things like work requirements, which has gotten a lot of support from moderate Republicans. The only way that that produces savings is if people come off Medicaid as a result. Work requirements in and of themselves are not saving any money. So I know advocates are very concerned about any level of cuts. I talked to somebody from a nursing home association who said: We can’t pick and choose. We’re not in a position to pick and choose which are better or worse, because at this point, everything on the table is bad for us. So I think people are definitely waiting with bated breath there.

Rovner: Yeah, I’ve heard a lot of Republicans over the last week or so with the talking points. If we’re just going after fraud and abuse then we’re not going to cut anybody’s benefits. And it’s like — um, good luck with that.

Goldman: And President Trump has said that as well.

Rovner: That’s right. Well, one place Congress could recoup a lot of money from Medicaid is by cracking down on provider taxes, which 49 of the 50 states use to plump up their federal Medicaid match, if you will. Basically the state levies a tax on hospitals or nursing homes or some other group of providers, claims that money as their state share to draw down additional federal matching Medicaid funds, then returns it to the providers in the form of increased reimbursement while pocketing the difference. You can call it money laundering as some do, or creative financing as others do, or just another way to provide health care to low-income people.

But one thing it definitely is, at least right now, is legal. Congress has occasionally tried to crack down on it since the late 1980s. I have spent way more time covering this fight than I wish I had, but the combination of state and health provider pushback has always prevented it from being eliminated entirely. If you want a really good backgrounder, I point you to the excellent piece in The New York Times this week by our podcast pals Margot Sanger-Katz and Sarah Kliff. What are you guys hearing about provider taxes and other forms of state contributions and their future in all of this? Is this where they’re finally going to look to get a pot of money?

Raman: It’s still in the mix. The tricky thing is how narrow the margins are, and when you have certain moderates having a hard line saying, I don’t want to cut more than $500 billion or $600 billion, or something like that. And then you have others that don’t want to dip below the $880 billion set for the Energy and Commerce Committee. And then there are others that have said it’s not about a specific number, it’s what is being cut. So I think once we have some more numbers for some of the other things, it’ll provide a better idea of what else can fit in. Because right now for work requirements, we’re going based on some older CBO [Congressional Budget Office] numbers. We have the CBO numbers that the Democrats asked for, but it doesn’t include everything. And piecing that together is the puzzle, will illuminate some of that, if there are things that people are a little bit more on board with. But it’s still kind of soon to figure out if we’re not going to see draft text until early next week.

Goldman: I think the tricky thing with provider taxes is that it’s so baked into the way that Medicaid functions in each state. And I think I totally co-sign on the New York Times article. It was a really helpful explanation of all of this, and I would bet that you’ll see a lot of pushback from state governments, including Republicans, on a proposal that makes severe changes to that.

Rovner: Someday, but not today, I will tell the story of the 1991 fight over this in which there was basically a bizarre dealmaking with individual senators to keep this legal. That was a year when the Democrats were trying to get rid of it. So it’s a bipartisan thing. All right, well, moving on.

It wouldn’t be a Thursday morning if we didn’t have breaking federal health personnel news. Today was supposed to be the confirmation hearing for surgeon general nominee and Fox News contributor Janette Nesheiwat. But now her nomination has been pulled over some questions about whether she was misrepresenting her medical education credentials, and she’s already been replaced with the nomination of Casey Means, the sister of top [Health and Human Services] Secretary [Robert F.] Kennedy [Jr.] aide Calley Means, who are both leaders in the MAHA [“Make America Healthy Again”] movement. This feels like a lot of science deniers moving in at one time. Or is it just me?

Edney: Yeah, I think that the Meanses have been in this circle, names floated for various things at various times, and this was a place where Casey Means fit in. And certainly she espouses a lot of the views on, like, functional medicine and things that this administration, at least RFK Jr., seems to also subscribe to. But the one thing I’m not as clear on her is where she stands with vaccines, because obviously Nesheiwat had fudged on her school a little bit, and—

Rovner: Yeah, I think she did her residency at the University of Arkansas—

Edney: That’s where.

Rovner: —and she implied that she’d graduated from the University of Arkansas medical school when in fact she graduated from an accredited Caribbean medical school, which lots of doctors go to. It’s not a sin—

Edney: Right.

Rovner: —and it’s a perfectly, as I say, accredited medical school. That was basically — but she did fudge it on her resume.

Edney: Yeah.

Rovner: So apparently that was one of the things that got her pulled.

Edney: Right. And the other, kind of, that we’ve seen in recent days, again, is Laura Loomer coming out against her because she thinks she’s not anti-vaccine enough. So what the question I think to maybe be looking into today and after is: Is Casey Means anti-vaccine enough for them? I don’t know exactly the answer to that and whether she’ll make it through as well.

Rovner: Well, we also learned this week that Vinay Prasad, a controversial figure in the covid movement and even before that, has been named to head the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] Center for Biologics and Evaluation Research, making him the nation’s lead vaccine regulator, among other things. Now he does have research bona fides but is a known skeptic of things like accelerated approval of new drugs, and apparently the biotech industry, less than thrilled with this pick, Anna?

Edney: Yeah, they are quite afraid of this pick. You could see it in the stocks for a lot of vaccine companies, for some other companies particularly. He was quite vocal and quite against the covid vaccines during covid and even compared them to the Nazi regime. So we know that there could be a lot of trouble where, already, you know, FDA has said that they’re going to require placebo-controlled trials for new vaccines and imply that any update to a covid vaccine makes it a new vaccine. So this just spells more trouble for getting vaccines to market and quickly to people. He also—you mentioned accelerated approval. This is a way that the FDA uses to try to get promising medicines to people faster. There are issues with it, and people have written about the fact that they rely on what are called surrogate endpoints. So not Did you live longer? but Did your tumor shrink?

And you would think that that would make you live longer, but it actually turns out a lot of times it doesn’t. So you maybe went through a very strong medication and felt more terrible than you might have and didn’t extend your life. So there’s a lot of that discussion, and so that. There are other drugs. Like this Sarepta drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy is a big one that Vinay Prasad has come out against, saying that should have never been approved, because it was using these kind of surrogate endpoints. So I think biotech’s pretty — thinking they’re going to have a lot tougher road ahead to bring stuff to market.

Rovner: And I should point out that over the very long term, this has been the continuing struggle at FDA. It’s like, do you protect the public but make people wait longer for drugs or do you get the drugs out and make sure that people who have no other treatments available have something available? And it’s been a constant push and pull. It’s not really been partisan. Sometimes you get one side pushing and the other side pushing back. It’s really nothing new. It’s just the sort of latest iteration of this.

Edney: Right. Yeah. This is the pendulum swing, back to the Maybe we need to be slowing it down side. It’s also interesting because there are other discussions from RFK Jr. that, like, We need to be speeding up approvals and Trump wants to speed up approvals. So I don’t know where any of this will actually come down when the rubber meets the road, I guess.

Rovner: Sandhya and Maya, I see you both nodding. Do you want to add something?

Raman: I think this was kind of a theme that I also heard this week in the — we had the Senate Finance hearing for some of the HHS [Department of Health and Human Services] nominees, and Jim O’Neill, who’s one of the nominees, that was something that was brought up by Finance ranking member Ron Wyden, that some of his past remarks when he was originally considered to be on the short list for FDA commissioner last Trump administration is that he basically said as long as it’s safe, it should go ahead regardless of efficacy. So those comments were kind of brought back again, and he’s in another hearing now, so that might come up as an issue in HELP [the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions] today.

Rovner: And he’s the nominee for deputy secretary, right? Have to make sure I keep all these things straight. Maya, you wanting to add something?

Goldman: Yeah, I was just going to say, I think there is a divide between these two philosophies on pharmaceuticals, and my sense is that the selection of Prasad is kind of showing that the anti-accelerated-approval side is winning out. But I think Anna is correct that we still don’t know where it’s going to land.

Rovner: Yes, and I will point out that accelerated approval first started during AIDS when there was no treatments and basically people were storming the — literally physically storming — the FDA, demanding access to AIDS drugs, which they did finally get. But that’s where accelerated approval came from. This is not a new fight, and it will continue.

Turning to abortion, the Trump administration surprised a lot of people this week when it continued the Biden administration’s position asking for that case in Texas challenging the abortion pill to be dropped. For those who’ve forgotten, this was a case originally filed by a bunch of Texas medical providers demanding the judge overrule the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone in the year 2000. The Supreme Court ruled the original plaintiff lacked standing to sue, but in the meantime, three states —Missouri, Idaho, and Kansas — have taken their place as plaintiffs. But now the Trump administration points out that those states have no business suing in the Northern District of Texas, which kind of seems true on its face. But we should not mistake this to think that the Trump administration now supports the current approval status of the abortion bill. Right, Sandhya?

Raman: Yeah, I think you’re exactly right. It doesn’t surprise me. If they had allowed these three states, none of which are Texas — they shouldn’t have standing. And if they did allow them to, that would open a whole new can of worms for so many other cases where the other side on so many issues could cherry-pick in the same way. And so I think, I assume, that this will come up in future cases for them and they will continue with the positions they’ve had before. But this was probably in their best interest not to in this specific one.

Rovner: Yeah. There are also those who point out that this could be a way of the administration protecting itself. If it wants to roll back or reimpose restrictions on the abortion pill, it would help prevent blue states from suing to stop that. So it serves a double purpose here, right?

Raman: Yeah. I couldn’t see them doing it another way. And even if you go through the ruling, the language they use, it’s very careful. It’s not dipping into talking fully about abortion. It’s going purely on standing. Yeah.

Rovner: There’s nothing that says, We think the abortion pill is fine the way it is. It clearly does not say that, although they did get the headlines — and I’m sure the president wanted — that makes it look like they’re towing this middle ground on abortion, which they may be but not necessarily in this case.

Well, before we move off of reproductive health, a shoutout here to the incredible work of ProPublica, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for public service this week for its stories on women who died due to abortion bans that prevented them from getting care for their pregnancy complications. Regular listeners of the podcast will remember that we talked about these stories as they came out last year, but I will post another link to them in the show notes today.

OK, moving on. There’s even more drug price news this week, starting with the return of, quote, “most favored nation” drug pricing. Anna, remind us what this is and why it’s controversial.

Edney: Yeah. So the idea of most favored nation, this is something President Trump has brought up before in his first administration, but it creates a basket, essentially, of different prices that nations pay. And we’re going to base ours on the lowest price that is paid for—

Rovner: We’re importing other countries’—

Edney: —prices.

Rovner: —price limits.

Edney: Yeah. Essentially, yes. We can’t import their drugs, but we can import their prices. And so the goal is to just basically piggyback off of whoever is paying the lowest price and to base ours off of that. And clearly the drug industry does not like this and, I think, has faced a number of kind of hits this week where things are looming that could really come after them. So Politico broke that news that Trump is going to sign or expected to sign an executive order that will direct his agencies to look into this most-favored-nation effort. And it feels very much like 2.0, like we were here before. And it didn’t exactly work out, obviously.

Rovner: They sued, didn’t they? The drug industry sued, as I recall.

Edney: Yeah, I think you’re right. Yes.

Goldman: If I’m remembering—

Rovner: But I think they won.

Goldman: If I’m remembering correctly, it was an Administrative Procedure Act lawsuit though, right? So—

Rovner: It was. Yes. It was about a regulation. Yes.

Goldman: —who knows what would happen if they go through a different procedure this time.

Rovner: So the other thing, obviously, that the drug industry is freaked out about right now are tariffs, which have been on again, off again, on again, off again. Where are we with tariffs on — and it’s not just tariffs on drugs being imported. It’s tariffs on drug ingredients being imported, right?

Edney: Yeah. And that’s a particularly rough one because many ingredients are imported, and then some of the drugs are then finished here, just like a car. All the pieces are brought in and then put together in one place. And so this is something the Trump administration has began the process of investigating. And PhRMA [Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America], the trade group for the drug industry, has come out officially, as you would expect, against the tariffs, saying that: This will reduce our ability to do R&D. It will raise the price of drugs that Americans pay, because we’re just going to pass this on to everyone. And so we’re still in this waiting zone of seeing when or exactly how much and all of that for the tariffs for pharma.

Rovner: And yet Americans are paying — already paying — more than they ever have. Maya, you have a story just about that. Tell us.

Goldman: Yeah, there was a really interesting report from an analytics data firm that showed the price that Americans are paying for prescriptions is continuing to climb. Also, the number of prescriptions that Americans are taking is continuing to climb. It certainly will be interesting to see if this administration can be any more successful. That report, I don’t think this made it into the article that I ended up writing, but it did show that the cost of insulin is down. And that’s something that has been a federal policy intervention. We haven’t seen a lot of the effects yet of the Medicare drug price negotiations, but I think there are signs that that could lower the prices that people are paying. So I think it’s interesting to just see the evolution of all of this. It’s very much in flux.

Rovner: A continuing effort. Well, we are now well into the second hundred days of Trump 2.0, and we’re still learning about the cuts to health and health-related programs the administration is making. Just in this week’s rundown are stories about hundreds more people being laid off at the National Cancer Institute, a stop-work order at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases research lab at Fort Detrick, Maryland, that studies Ebola and other deadly infectious diseases, and the layoff of most of the remaining staff at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

A reminder that this is all separate from the discretionary-spending budget request that the administration sent up to lawmakers last week. That document calls for a 26% cut in non-mandatory funding at HHS, meaning just about everything other than Medicare and Medicaid. And it includes a proposed $18 billion cut to the NIH [National Institutes of Health] and elimination of the $4 billion Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which helps millions of low-income Americans pay their heating and air conditioning bills. Now, this is normally the part of the federal budget that’s deemed dead on arrival. The president sends up his budget request, and Congress says, Yeah, we’re not doing that. But this at least does give us an idea of what direction the administration wants to take at HHS, right? What’s the likelihood of Congress endorsing any of these really huge, deep cuts?

Raman: From both sides—

Rovner: Go ahead, Sandhya.

Raman: It’s not going to happen, and they need 60 votes in the Senate to pass the appropriations bills. I think that when we’re looking in the House in particular, there are a lot of things in what we know from this so-called skinny budget document that they could take up and put in their bill for Labor, HHS, and Education. But I think the Senate’s going to be a different story, just because the Senate Appropriations chair is Susan Collins and she, as soon as this came out, had some pretty sharp words about the big cuts to NIH. They’ve had one in a series of two hearings on biomedical research. Concerned about some of these kinds of things. So I cannot necessarily see that sharp of a cut coming to fruition for NIH, but they might need to make some concessions on some other things.

This is also just a not full document. It has some things and others. I didn’t see any to FDA in there at all. So that was a question mark, even though they had some more information in some of the documents that had leaked kind of earlier on a larger version of this budget request. So I think we’ll see more about how people are feeling next week when we start having Secretary Kennedy testify on some of these. But I would not expect most of this to make it into whatever appropriations law we get.

Goldman: I was just going to say that. You take it seriously but not literally, is what I’ve been hearing from people.

Edney: We don’t have a full picture of what has already been cut. So to go in and then endorse cutting some more, maybe a little bit too early for that, because even at this point they’re still bringing people back that they cut. They’re finding out, Oh, this is actually something that is really important and that we need, so to do even more doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense right now.

Rovner: Yeah, that state of disarray is purposeful, I would guess, and doing a really good job at sort of clouding things up.

Goldman: One note on the cuts. I talked to someone at HHS this week who said as they’re bringing back some of these specialized people, in order to maintain the legality of, what they see as the legality of, the RIF [reduction in force], they need to lay off additional people to keep that number consistent. So I think that is very much in flux still and interesting to watch.

Rovner: Yeah, and I think that’s part of what we were seeing this week is that the groups that got spared are now getting cut because they’ve had to bring back other people. And as I point out, I guess, every week, pretty much all of this is illegal. And as it goes to courts, judges say, You can’t do this. So everything is in flux and will continue.

All right, finally this week, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who as of now is scheduled to appear before the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee next week to talk about the department’s proposed budget, is asking CDC [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] to develop new guidance for treating measles with drugs and vitamins. This comes a week after he ordered a change in vaccine policy you already mentioned, Anna, so that new vaccines would have to be tested against placebos rather than older versions of the vaccine. These are all exactly the kinds of things that Kennedy promised health committee chairman Bill Cassidy he wouldn’t do. And yet we’ve heard almost nothing from Cassidy about anything the secretary has said or done since he’s been in office. So what do we expect to happen when they come face-to-face with each other in front of the cameras next week, assuming that it happens?

Edney: I’m very curious. I don’t know. Do I expect a senator to take a stand? I don’t necessarily, but this—

Rovner: He hasn’t yet.

Edney: Yeah, he hasn’t yet. But this is maybe about face-saving too for him. So I don’t know.

Rovner: Face-saving for Kennedy or for Cassidy?

Edney: For Cassidy, given he said: I’m going to keep an eye on him. We’re going to talk all the time, and he is not going to do this thing without my input. I’m not sure how Cassidy will approach that. I think it’ll be a really interesting hearing that we’ll all be watching.

Rovner: Yes. And just little announcement, if it does happen, that we are going to do sort of a special Wednesday afternoon after the hearing with some of our KFF Health News colleagues. So we are looking forward to that hearing. All right, that is this week’s news. Now we will play my “Bill of the Month” interview with Lauren Sausser, and then we will come back and do our extra credits.

I am pleased to welcome back to the podcast KFF Health News’ Lauren Sausser, who co-reported and wrote the latest KFF Health News “Bill of the Month.” Lauren, welcome back.

Lauren Sausser: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Rovner: So this month’s patient got preventive care, which the Affordable Care Act was supposed to incentivize by making it cost-free at the point of service — except it wasn’t. Tell us who the patient is and what kind of care they got.

Sausser: Carmen Aiken is from Chicago. Carmen uses they/them pronouns. And Carmen made an appointment in the summer of 2023 for an annual checkup. This is just like a wellness check that you are very familiar with. You get your vaccines updated. You get your weight checked. You talk to your doctor about your physical activity and your family history. You might get some blood work done. Standard stuff.

Rovner: And how big was the bill?

Sausser: The bill ended up being more than $1,400 when it should, in Carmen’s mind, have been free.

Rovner: Which is a lot.

Sausser: A lot.

Rovner: I assume that there was a complaint to the health plan and the health plan said, Nope, not covered. Why did they say that?

Sausser: It turns out that alongside with some blood work that was preventive, Carmen also had some blood work done to monitor an ongoing prescription. Because that blood test is not considered a standard preventive service, the entire appointment was categorized as diagnostic and not preventive. So all of these services that would’ve been free to them, available at no cost, all of a sudden Carmen became responsible for.

Rovner: So even if the care was diagnostic rather than strictly preventive — obviously debatable — that sounds like a lot of money for a vaccine and some blood test. Why was the bill so high?

Sausser: Part of the reason the bill was so high was because Carmen’s blood work was sent to a hospital for processing, and hospitals, as you know, can charge a lot more for the same services. So under Carmen’s health plan, they were responsible for, I believe it was, 50% of the cost of services performed in an outpatient hospital setting. And that’s what that blood work fell under. So the charges were high.

Rovner: So we’ve talked a lot on the podcast about this fight in Congress to create site-neutral payments. This is a case where that probably would’ve made a big difference.

Sausser: Yeah, it would. And there’s discussion, there’s bipartisan support for it. The idea is that you should not have to pay more for the same services that are delivered at different places. But right now there’s no legislation to protect patients like Carmen from incurring higher charges.

Rovner: So what eventually happened with this bill?

Sausser: Carmen ended up paying it. They put it on a credit card. This was of course after they tried appealing it to their insurance company. Their insurance company decided that they agreed with the provider that these services were diagnostic, not preventive. And so, yeah, Carmen was losing sleep over this and decided ultimately that they were just going to pay it.

Rovner: And at least it was a four-figure bill and not a five-figure bill.

Sausser: Right.

Rovner: What’s the takeaway here? I imagine it is not that you should skip needed preventive/diagnostic care. Some drugs, when you’re on them, they say that you should have blood work done periodically to make sure you’re not having side effects.

Sausser: Right. You should not skip preventive services. And that’s the whole intent behind this in the ACA. It catches stuff early so that it becomes more treatable. I think you have to be really, really careful and specific when you’re making appointments, and about your intention for the appointment, so that you don’t incur charges like this. I think that you can also be really careful about where you get your blood work conducted. A lot of times you’ll see these signs in the doctor’s office like: We use this lab. If this isn’t in-network with you, you need to let us know. Because the charges that you can face really vary depending on where those labs are processed. So you can be really careful about that, too.

Rovner: And adding to all of this, there’s the pending Supreme Court case that could change it, right?

Sausser: Right. The Supreme Court heard oral arguments. It was in April. I think it was on the 21st. And it is a case that originated out in Texas. There is a group of Christian businesses that are challenging the mandate in the ACA that requires health insurers to cover a lot of these preventive services. So obviously we don’t have a decision in the case yet, but we’ll see.

Rovner: We will, and we will cover it on the podcast. Lauren Sausser, thank you so much.

Sausser: Thank you.

Rovner: OK, we’re back. Now it’s time for our extra-credit segment. That’s where we each recognize the story we read this week we think you should read, too. Don’t worry if you miss it. We will put the links in our show notes on your phone or other mobile device. Maya, you were the first to choose this week, so why don’t you go first?

Goldman: My extra credit is from Stat. It’s called “Europe Unveils $565 Million Package To Retain Scientists, and Attract New Ones,” by Andrew Joseph. And I just think it’s a really interesting evidence point to the United States’ losses, other countries’ gain. The U.S. has long been the pinnacle of research science, and people flock to this country to do research. And I think we’re already seeing a reversal of that as cuts to NIH funding and other scientific enterprises is reduced.

Rovner: Yep. A lot of stories about this, too. Anna.

Edney: So mine is from a couple of my colleagues that they did earlier this week. “A Former TV Writer Found a Health-Care Loophole That Threatens To Blow Up Obamacare.” And I thought it was really interesting because it had brought me back to these cheap, bare-bones plans that people were allowed to start selling that don’t meet any of the Obamacare requirements. And so this guy who used to, in the ’80s and ’90s, wrote for sitcoms — “Coach” or “Night Court,” if anyone goes to watch those on reruns. But he did a series of random things after that and has sort of now landed on selling these junk plans, but doing it in a really weird way that signs people up for a job that they don’t know they’re being signed up for. And I think it’s just, it’s an interesting read because we knew when these things were coming online that this was shady and people weren’t going to get the coverage they needed. And this takes it to an extra level. They’re still around, and they’re still ripping people off.

Rovner: Or as I’d like to subhead this story: Creative people think of creative things.

Edney: “Creative” is a nice word.

Rovner: Sandhya.

Raman: So my pick is “In the Deep South, Health Care Fights Echo Civil Rights Battles,” and it’s from Anna Claire Vollers at the Louisiana Illuminator. And her story looks at some of the ties between civil rights and health. So 2025 is the 70th anniversary of the bus boycott, the 60th anniversary of Selma-to-Montgomery marches, the Voting Rights Act. And it’s also the 60th anniversary of Medicaid. And she goes into, Medicaid isn’t something you usually consider a civil rights win, but health as a human right was part of the civil rights movement. And I think it’s an interesting piece.

Rovner: It is an interesting piece, and we should point out Medicare was also a huge civil rights, important piece of law because it desegregated all the hospitals in the South. All right, my extra credit this week is a truly infuriating story from NPR by Andrea Hsu. It’s called “Fired, Rehired, and Fired Again: Some Federal Workers Find They’re Suddenly Uninsured.” And it’s a situation that if a private employer did it, Congress would be all over them and it would be making huge headlines. These are federal workers who are trying to do the right thing for themselves and their families but who are being jerked around in impossible ways and have no idea not just whether they have jobs but whether they have health insurance, and whether the medical care that they’re getting while this all gets sorted out will be covered. It’s one thing to shrink the federal workforce, but there is some basic human decency for people who haven’t done anything wrong, and a lot of now-former federal workers are not getting it at the moment.

OK, that is this week’s show. As always, if you enjoy the podcast, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. We’d appreciate if you left us a review. That helps other people find us, too. Thanks as always to our editor, Emmarie Huetteman, and our producer, Francis Ying. Also, as always, you can email us your comments or questions, We’re at whatthehealth@kff.org, or you can still find me on X, @jrovner, or on Bluesky, @julierovner. Where are you folks hanging these days? Sandhya?

Raman: I’m on X, @SandhyaWrites, and also on Bluesky, @SandhyaWrites at Bluesky.

Rovner: Anna.

Edney: X and Bluesky, @annaedney.

Rovner: Maya.

Goldman: I am on X, @mayagoldman_. Same on Bluesky and also increasingly on LinkedIn.

Rovner: All right, we’ll be back in your feed next week. Until then, be healthy.

Credits

Francis Ying

Audio producer

Emmarie Huetteman

Editor

To hear all our podcasts, click here.

And subscribe to KFF Health News’ “What the Health?” on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, or wherever you listen to podcasts.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

Despite Historic Indictment, Doctors Will Keep Mailing Abortion Pills Across State Lines

When the news broke on Jan. 31 that a New York physician had been indicted for shipping abortion medications to a woman in Louisiana, it stoked fear across the network of doctors and medical clinics who engage in similar work. “It’s scary. It’s frustrating,” said […]

PharmaceuticalsWhen the news broke on Jan. 31 that a New York physician had been indicted for shipping abortion medications to a woman in Louisiana, it stoked fear across the network of doctors and medical clinics who engage in similar work.

“It’s scary. It’s frustrating,” said Angel Foster, co-founder of the Massachusetts Medication Abortion Access Project, a clinic near Boston that mails mifepristone and misoprostol pills to patients in states with abortion bans. But, Foster added, “it’s not entirely surprising.”

Ever since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, abortion providers like her had been expecting prosecution or another kind of legal challenge from states with abortion bans, she said.

“It was unclear when those tests would come, and would it be against an individual provider or a practice or organization?” she said. “Would it be a criminal indictment, or would it be a civil lawsuit,” or even an attack on licensure? she wondered. “All of that was kind of unknown, and we’re starting to see some of this play out.”

The indictment also sparked worry among abortion providers like Kohar Der Simonian, medical director for Maine Family Planning. The clinic doesn’t mail pills into states with bans, but it does treat patients who travel from those states to Maine for abortion care.

“It just hit home that this is real, like this could happen to anybody, at any time now, which is scary,” Der Simonian said.

Der Simonian and Foster both know the indicted doctor, Margaret Carpenter.

“I feel for her. I very much support her,” Foster said. “I feel very sad for her that she has to go through all of this.”

On Jan. 31, Carpenter became the first U.S. doctor criminally charged for providing abortion pills across state lines — a medical practice that grew after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision on June 24, 2022, which overturned Roe.

Since Dobbs, 12 states have enacted near-total abortion bans, and an additional 10 have outlawed the procedure after a certain point in pregnancy, but before a fetus is viable.

Carpenter was indicted alongside a Louisiana mother who allegedly received the mailed package and gave the pills prescribed by Carpenter to her minor daughter.

The teen wanted to keep the pregnancy and called 911 after taking the pills, according to an NPR and KFF Health News interview with Tony Clayton, the Louisiana local district attorney prosecuting the case. When police responded, they learned about the medication, which carried the prescribing doctor’s name, Clayton said.

On Feb. 11, Louisiana’s Republican governor, Jeff Landry, signed an extradition warrant for Carpenter. He later posted a video arguing she “must face extradition to Louisiana, where she can stand trial and justice will be served.”

New York’s Democratic governor, Kathy Hochul, countered by releasing her own video, confirming she was refusing to extradite Carpenter. The charges carry a possible five-year prison sentence.

“Louisiana has changed their laws, but that has no bearing on the laws here in the state of New York,” Hochul said.

Eight states — New York, Maine, California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington — have passed laws since 2022 to protect doctors who mail abortion pills out of state, and thereby block or “shield” them from extradition in such cases. But this is the first criminal test of these relatively new “shield laws.”

The telemedicine practice of consulting with remote patients and prescribing them medication abortion via the mail has grown in recent years — and is now playing a critical role in keeping abortion somewhat accessible in states with strict abortion laws, according to research from the Society of Family Planning, a group that supports abortion access.

Doctors who prescribe abortion pills across state lines describe facing a new reality in which the criminal risk is no longer hypothetical. The doctors say that if they stop, tens of thousands of patients would no longer be able to end early pregnancies safely at home, under the care of a U.S. physician. But the doctors could end up in the crosshairs of a legal clash over the interstate practice of medicine when two states disagree on whether people have a right to end a pregnancy.

Doctors on Alert but Remain Defiant

Maine Family Planning, a network of clinics across 19 locations, offers abortions, birth control, gender-affirming care, and other services. One patient recently drove over 17 hours from South Carolina, a state with a six-week abortion ban, Der Simonian said.

For Der Simonian, that case illustrates how desperate some of the practice’s patients are for abortion access. It’s why she supported Maine’s 2024 shield law, she said.

Maine Family Planning has discussed whether to start mailing abortion medication to patients in states with bans, but it has decided against it for now, according to Kat Mavengere, a clinic spokesperson.

Reflecting on Carpenter’s indictment, Der Simonian said it underscored the stakes for herself — and her clinic — of providing any abortion care to out-of-state patients. Shield laws were written to protect against the possibility that a state with an abortion ban charges and tries to extradite a doctor who performed a legal, in-person procedure on someone who had traveled there from another state, according to a review of shield laws by the Center on Reproductive Health, Law, and Policy at the UCLA School of Law.

“It is a fearful time to do this line of work in the United States right now,” Der Simonian said. “There will be a next case.” And even though Maine’s shield law protects abortion providers, she said, “you just don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Data shows that in states with total or six-week abortion bans, an average of 7,700 people a month were prescribed and took mifepristone and misoprostol to end their pregnancies by out-of-state doctors practicing in states with shield laws. The data, covering the second quarter of 2024, is part of a #WeCount report estimating the volume and types of abortions in the U.S., conducted by the Society of Family Planning.

Among Louisiana residents, nearly 60% of abortions took place via telemedicine in the second half of 2023 (the most recent period for which estimates are available), giving Louisiana the highest rate of telemedicine abortions among states that passed strict bans after Dobbs, according to the #WeCount survey.

Organizations like the Massachusetts Medication Abortion Access Project, known as the MAP, are responding to the demand for remote care. The MAP was launched after the Dobbs ruling, with the mission of writing prescriptions for patients in other states.

During 2024, the MAP says, it was mailing abortion medications to about 500 patients a month. In the new year, the monthly average has grown to 3,000 prescriptions a month, said Foster, the group’s co-founder.

The majority of the MAP’s patients — 80% — live in Texas or states in the Southeast, a region blanketed with near-total abortion restrictions, Foster said.

But the recent indictment from Louisiana will not change the MAP’s plans, Foster said. The MAP currently has four staff doctors and is hiring one more.

“I think there will be some providers who will step out of the space, and some new providers will step in. But it has not changed our practice,” Foster said. “It has not changed our intention to continue to practice.”

The MAP’s organizational structure was designed to spread potential liability, Foster said.

“The person who orders the pills is different than the person who prescribes the pills, is different from the person who ships the pills, is different from the person who does the payments,” she explained.

In 22 states and Washington, D.C., Democratic leaders helped establish shield laws or similarly protective executive orders, according to the UCLA School of Law review of shield laws.

The review found that in eight states, the shield law applies to in-person and telemedicine abortions. In the other 14 states plus Washington, D.C., the protections do not explicitly extend to abortion via telemedicine.

Most of the shield laws also apply to civil lawsuits against doctors. Over a month before Louisiana indicted Carpenter, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a civil suit against her. A Texas judge ruled against Carpenter on Feb. 13, imposing penalties of more than $100,000.

By definition, state shield laws cannot protect doctors when they leave the state. If they move or even travel elsewhere, they lose the first state’s protection and risk arrest in the destination state, and maybe extradition to a third state.

Physicians doing this type of work accept there are parts of the U.S. where they should no longer go, said Julie F. Kay, a human rights lawyer who helps doctors set up telemedicine practices.

“There’s really a commitment not to visit those banned and restricted states,” said Kay, who worked with Carpenter to help start the Abortion Coalition for Telemedicine.

“We didn’t have anybody going to the Super Bowl or Mardi Gras or anything like that,” Kay said of the doctors who practice abortion telemedicine across state lines.

She said she has talked to other interested doctors who decided against doing it “because they have an elderly parent in Florida, or a college student somewhere, or family in the South.” Any visits, even for a relative’s illness or death, would be too risky.

“I don’t use the word ‘hero’ lightly or toss it around, but it’s a pretty heroic level of providing care,” Kay said.

Governors Clash Over Doctor’s Fate

Carpenter’s case remains unresolved. New York’s rebuff of Louisiana’s extradition request shows the state’s shield law is working as designed, according to David Cohen and Rachel Rebouché, law professors with expertise in abortion laws.

Louisiana officials, for their part, have pushed back in social media posts and media interviews.

“It is not any different than if she had sent fentanyl here. It’s really not,” Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill told Fox 8 News in New Orleans. “She sent drugs that are illegal to send into our state.”

Louisiana’s next step would be challenging New York in federal courts, according to legal experts across the political spectrum.

NPR and KFF Health News asked Clayton, the Louisiana prosecutor who charged Carpenter, whether Louisiana has plans to do that. Clayton declined to answer.

Case Highlights Fraught New Legal Frontier

A major problem with the new shield laws is that they challenge the basic fabric of U.S. law, which relies on reciprocity between states, including in criminal cases, said Thomas Jipping, a senior legal fellow with the Heritage Foundation, which supports a national abortion ban.

“This actually tries to undermine another state’s ability to enforce its own laws, and that’s a very grave challenge to this tradition in our country,” Jipping said. “It’s unclear what legal issues, or potentially constitutional issues, it may raise.”

But other legal scholars disagree with Jipping’s interpretation. The U.S. Constitution requires extradition only for those who commit crimes in one state and then flee to another state, said Cohen, a law professor at Drexel University’s Thomas R. Kline School of Law.

Telemedicine abortion providers aren’t located in states with abortion bans and have not fled from those states — therefore they aren’t required to be extradited back to those states, Cohen said. If Louisiana tries to take its case to federal court, he said, “they’re going to lose because the Constitution is clear on this.”

“The shield laws certainly do undermine the notion of interstate cooperation, and comity, and respect for the policy choices of each state,” Cohen said, “but that has long been a part of American law and history.”

When states make different policy choices, sometimes they’re willing to give up those policy choices to cooperate with another state, and sometimes they’re not, he said.

The conflicting legal theories will be put to the test if this case goes to federal court, other legal scholars said.

“It probably puts New York and Louisiana in real conflict, potentially a conflict that the Supreme Court is going to have to decide,” said Rebouché, dean of the Temple University Beasley School of Law.

Rebouché, Cohen, and law professor Greer Donley worked together to draft a proposal for how state shield laws might work. Connecticut passed the first law — though it did not include protections specifically for telemedicine. It was signed by the state’s governor in May 2022, over a month before the Supreme Court overturned Roe, in anticipation of potential future clashes between states over abortion rights.

In some shield-law states, there’s a call to add more protections in response to Carpenter’s indictment.

New York state officials have. On Feb. 3, Hochul signed a law that allows physicians to name their clinic as the prescriber — instead of using their own names — on abortion medications they mail out of state. The intent is to make it more difficult to indict individual doctors. Der Simonian is pushing for a similar law in Maine.

Samantha Glass, a family medicine physician in New York, has written such prescriptions in a previous job, and plans to find a clinic where she could offer that again. Once a month, she travels to a clinic in Kansas to perform in-person abortions.

Carpenter’s indictment could cause some doctors to stop sending pills to states with bans, Glass said. But she believes abortion should be as accessible as any other health care.

“Someone has to do it. So why wouldn’t it be me?” Glass said. “I just think access to this care is such a lifesaving thing for so many people that I just couldn’t turn my back on it.”

This article is from a partnership that includes WWNO, NPR, and KFF Health News.

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF—an independent source of health policy research, polling, and journalism. Learn more about KFF.

USE OUR CONTENT

This story can be republished for free (details).

by Admin

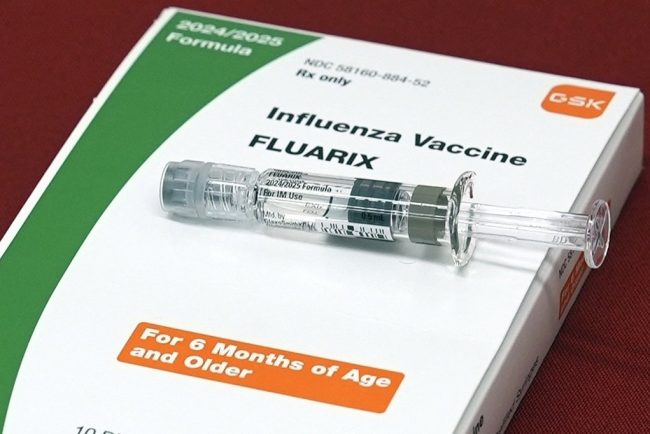

U.S. says more children died this flu season than in the past 15 years

The 216 pediatric deaths reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention eclipse the 207 reported last year and is the most since the 2009-10 swine flu pandemic.

Flu seasonThe 216 pediatric deaths reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention eclipse the 207 reported last year and is the most since the 2009-10 swine flu pandemic.

by Admin

Severe flu season may be causing rare brain complications in children, experts warn

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates 19,000 people have died from the flu so far this winter, including 86 children.

Flu seasonThe Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates 19,000 people have died from the flu so far this winter, including 86 children.

by Admin

Influenza is hitting hard. Data shows fewer Canadians got their flu shot

Most provinces and at least one territory report declines in people getting their flu shot compared to last year, with doctors warning of the strain it could pose to hospitals.

Flu seasonMost provinces and at least one territory report declines in people getting their flu shot compared to last year, with doctors warning of the strain it could pose to hospitals.

by Admin

Manitoba to see late peak in cold and flu season

So far this winter, 1,998 cases of influenza A have been reported. By this time in the 2023-2024 season, there had been 2723 cases.

Flu seasonSo far this winter, 1,998 cases of influenza A have been reported. By this time in the 2023-2024 season, there had been 2723 cases.

by Admin

The danger of bird flu mixing with human flu? A potential pandemic

As cases of seasonal influenza surge, health officials are closely monitoring a growing threat—the potential fusion of human and bird flu strains.

Flu seasonAs cases of seasonal influenza surge, health officials are closely monitoring a growing threat—the potential fusion of human and bird flu strains.

by Admin

The flu is on the rise in Canada. Here’s what to know

As of Feb. 1, 21.2 per cent of tests have come back positive for influenza. Since Aug. 25, 2024, a total of 76 influenza-associated deaths were reported in Canada.

Flu seasonAs of Feb. 1, 21.2 per cent of tests have come back positive for influenza. Since Aug. 25, 2024, a total of 76 influenza-associated deaths were reported in Canada.

by Admin

U.S. flu season sees 15-year peak in doctor visits

Of course, other viral infections can be mistaken for flu. But COVID-19 appears to be on the decline, according to hospital data and to CDC modeling projections.

Flu seasonOf course, other viral infections can be mistaken for flu. But COVID-19 appears to be on the decline, according to hospital data and to CDC modeling projections.